This month is a time to celebrate.

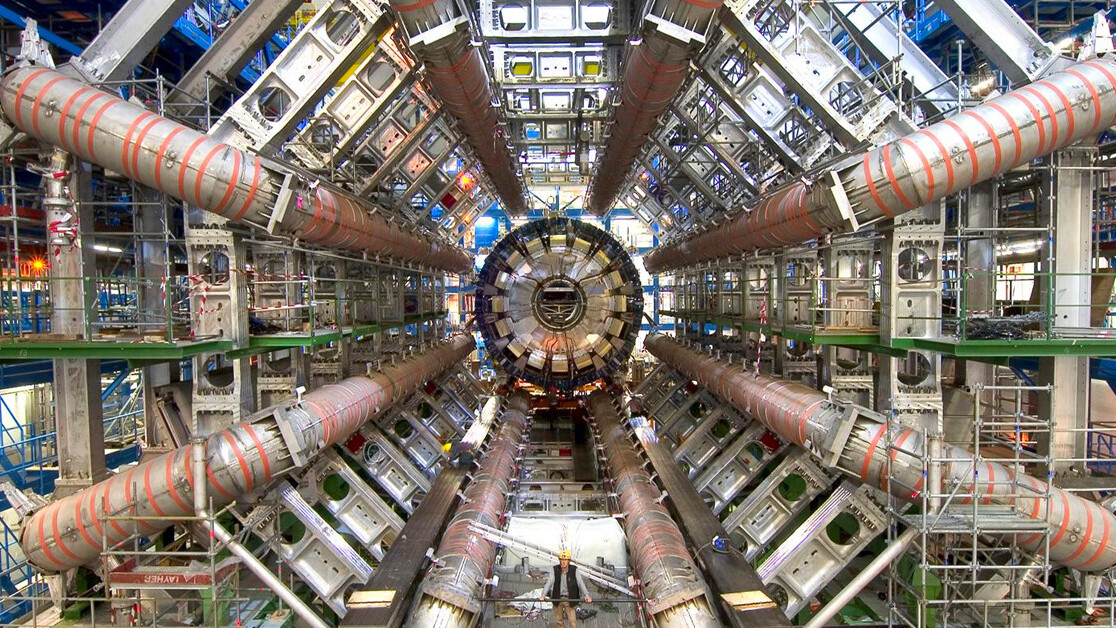

CERN has just announced the discovery offour brand-new particlesat the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) in Geneva.

That said, the theory is still far from being fully understood.

One of its most troublesome features is its description of the strong force which holds the atomic nucleus together.

It describes how quarks interact through the strong force by exchanging particles called gluons.

However, the way gluons interact with quarks makes the strong force behave very differently from electromagnetism.

Unless, of course, you smash them open at incredible speeds, as we are doing at CERN.

40% off TNW Conference!

This has been shownrepeatedly by experiments we have never seen a lone quark.

We therefore cannot (yet) prove theoretically that quarks cant exist on their own.

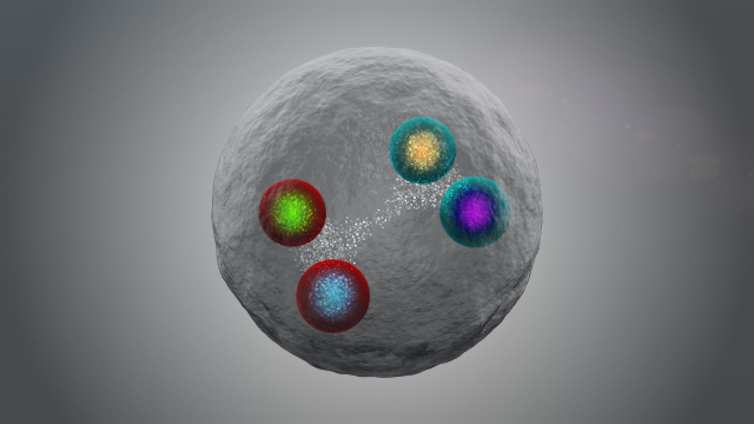

Illustration of a tetraquark.

For a long time, only baryons and mesons were seen in experiments.

But in 2003, the Belle experiment in Japandiscovered a particlethat didnt fit in anywhere.

It turned out to be the first of a long series of tetraquarks.

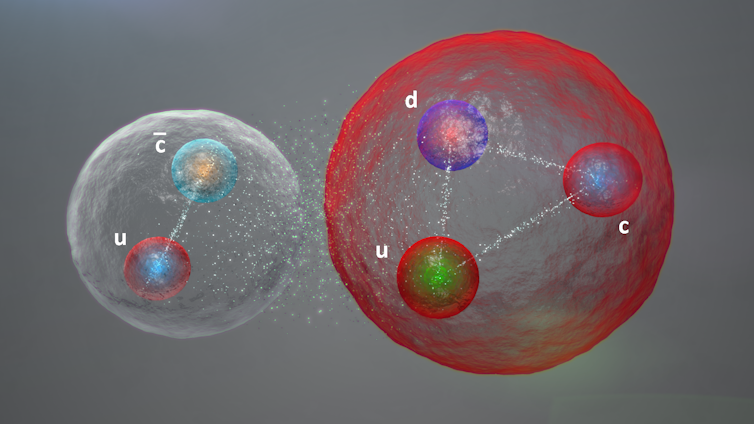

In 2015, the LHCb experiment at the LHCdiscovered two pentaquarks.

The four new particles weve discovered recentlyare all tetraquarkswith a charm quark pair and two other quarks.

All these objects are particles in the same way as the proton and the neutron are particles.

But they are not fundamental particles: quarks and electrons are the true building blocks of matter.

Charming new particles

The LHC has now discovered 59 new hadrons.

These include the tetraquarks most recently discovered, but also new mesons and baryons.

All these new particles contain heavy quarks such as charm and bottom.

These hadrons are interesting to study.

They also tell us what nature does not like.

For example, why do all tetra- and pentaquarks contain a charm-quark pair (with just one exception)?

And why are there no corresponding particles with strange-quark pairs?

There is currently no explanation.

CERN

Another mystery is how these particles are bound together by the strong force.

One school of theorists considers them to be compact objects, like the proton or the neutron.

Others claim they are akin to molecules formed by two loosely bound hadrons.

This helps bridge the gap between experiment and theory.

The more hadrons we can find, the better we can tune the models to the experimental facts.

Despite its successes, the standard model is certainly not the last word in the understanding of particles.

It is for instanceinconsistent with cosmological modelsdescribing the formation of the universe.

The LHC is searching for new fundamental particles that could explain these discrepancies.

These particles could be visible at the LHC, but hidden in the background of particle interactions.

Or they could show up as small quantum mechanical effects in known processes.

In either case, a better understanding of the strong force is needed to find them.