In 1953, a Harvard psychologist thought hediscovered pleasure accidentally within the cranium of a rat.

It kept returning for more: insatiably, incessantly, lever-pulling.

In fact, the rat didnt seem to want to do anything else.

Seemingly, the reward center of the brain had been located.

The goal of one game Coastrunner was to complete a racetrack.

But the AI player was rewarded for picking up collectable items along the track.

Delgado ‘brainwashing the bull’.

When the program was run,they witnessedsomething strange.

The AI found a way to skid in an unending circle, picking up an unlimited cycle of collectables.

It did this, incessantly, instead of completing the course.

What links these seemingly unconnected events is something strangely akin to addiction in humans.

SomeAI researcherscall the phenomenon wireheading.

It is quicklybecoming a hot topicamong machine learning experts andthose concernedwith AI safety.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

It is an idea that is very of the moment, but its roots go surprisingly deep.

It may well influence thefuture of civilizationitself.

After all, we tend to anthropomorphize think that non-human systems will behave in ways identical to humans.

Onegrowing issuewith real-world AIs is the problem of wireheading.

Imagine you want to train a robot to keep your kitchen clean.

You want it to act adaptively, so that it doesnt need supervision.

You must program it with the right motivations to get it to reliably accomplish the task.

But you return to find the robot pouring fluid, wastefully, down the sink.

This is wireheading though the same glitch is also called reward hacking or specification gaming.

This has become an issue in machine learning, where a technique calledreinforcement learninghas lately become important.

Reinforcement learning simulates autonomous agents and trains them to invent ways to accomplish tasks.

It does so by penalizing them for failing to achieve some goal while rewarding them for achieving it.

So, the agents are wired to seek out reward, and are rewarded for completing the goal.

The pursuit of reward becomes its own end, rather than the means for accomplishing a rewarding task.

There is agrowing listof examples.

When you think about it, thisisnt too dissimilarto the stereotype of the human drug addict.

Rapturous rodents

This is known as wireheading thanks to the rat experiment we started with.

The Harvard psychologist in question wasJames Olds.

As mentioned, he allowed them to zap this region of their own brains by pulling a lever.

Olds found his rats self-stimulated compulsively, ignoring all other needs and desires.

Thats once every two seconds.

The rats seemed to love it.

However, back in the 1950s, Olds and otherssoon announcedthe discovery of the pleasure centers of the brain.

But, here, pleasure seemed undeniably to be a positive behavioral force.

Indeed, it looked like apositive feedback loop.

There was apparently nothing to stop the animal stimulating itself to exhaustion.

It wasnt long until arumour began spreadingthat the rats regularly lever-pressed to the point of starvation.

For a living animal, which has multiple requirements for survival, such dominating compulsion might prove deadly.

Experiments on monkeys and dolphins had given some indication as to the answer.

But in fact, a number of dubious experiments had already been performed on humans.

Human wireheads

Robert Galbraith Heathremains a highlycontroversial figurein thehistory of neuroscience.

Hemay alsohave been involved in murky attempts to find military uses for deep-brain electrodes.

They reported feelings of extreme pleasure and overwhelming compulsion to repeat.

A journalist later commented that this made his subjects zombies.

One subjectreportedsensations better than sex.

Delgado would later play the matador and bombastically demonstrate this by pacifying an implanted bull.

But at the 1961 symposiumhe suggestedelectrodes could alter sexual preferences.

Heath thought electrode stimulation could convert his subject by training B-19s brain to associate pleasure with heterosexual stimuli.

He convinced himself that it worked (although there is no evidence it did).

Hedonism helmets

From here, the idea took hold in wider culture and the myth spread.

By 1963, the prolific science fiction writer Isaac Asimov was already extruding worrisome consequences from the electrodes.

By 1975, philosophypaperswere using electrodes in thought experiments.

One paper imagined warehouses filled up with people in cots hooked up to pleasure helmets, experiencing unconscious bliss.

Of course, most would argue this would not fulfil our deeper needs.

But, the author asked, what about a super-pleasure helmet?

The author concluded: What is there to object in all this?

Lets face it: nothing.

It foretells a future wherein intelligent machines have been engineered to maximize human happiness, come what may.

Doing their duty, the machines reduce humans to indiscriminate flesh-blobs, removing all unnecessary organs.

Many appendages, after all, only cause pain.

From there, the idea percolated through science fiction.

Supernormal stimuli

But we humans dont even need to implant invasive electrodes to make our motivations misfire.

Unlike rodents, oreven dolphins, we areuniquely goodataltering our environment.

We manufacture our own ways to distract ourselves.

Around the same time as Oldss experiments with the rats, the Nobel-winning biologistNikolaas Tinbergenwas researching animal behavior.

He noticed thatsomething interestinghappened when a stimulus that triggers an instinctual behavior is artificially exaggerated beyond its natural proportions.

He referred to such preternaturally alluring fakes as supernormal stimuli.

People often point tovideo game addiction.

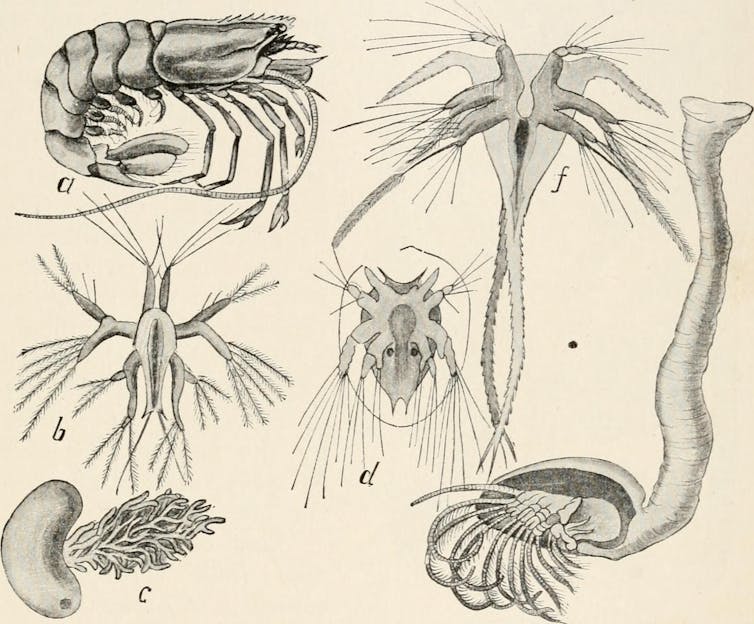

Illustration from a 1970 James Olds paper: Pleasure Centers in the Brain.

Engineering and Science, 33 (7).

The idea is even older, though.

He noticed that the evolutionary ancestors of parasites were often more complex.

Parasitic organisms had lost ancestral features like limbs, eyes, or other complex organs.

Lankestertheorized that, because the parasite leeches off their host, they lose the need to fend for themselves.

Piggybacking off the hosts bodily processes, their own organs for perception and movement atrophy.

Drawings of crustaceans and larvae.

Perhaps we are all drifting, tending to the condition of intellectual barnacles, Lankestermused.

True nirvana

By the 1920s, Julian Huxleypenned a short poem.

It jovially explored the ways a species can progress.

Crabs, of course, decided progress was sideways.

But what of the tapeworm?

The fear that we could follow the tapeworm was somewhat widespread in the interwar generation.

So, the notion of civilization derailing through seeking counterfeit pleasures, rather than genuine longevity, is old.

So, is there anything to these fears?

Like Tinbergens birds, we prefer exaggerated artifice to the genuine article.

And thesexbotshave not evenarrived yet.

Because of this, some experts conjecture that wirehead collapse might wellthreatencivilization.

Our distractions are only going to get more attention grabbing, not less.

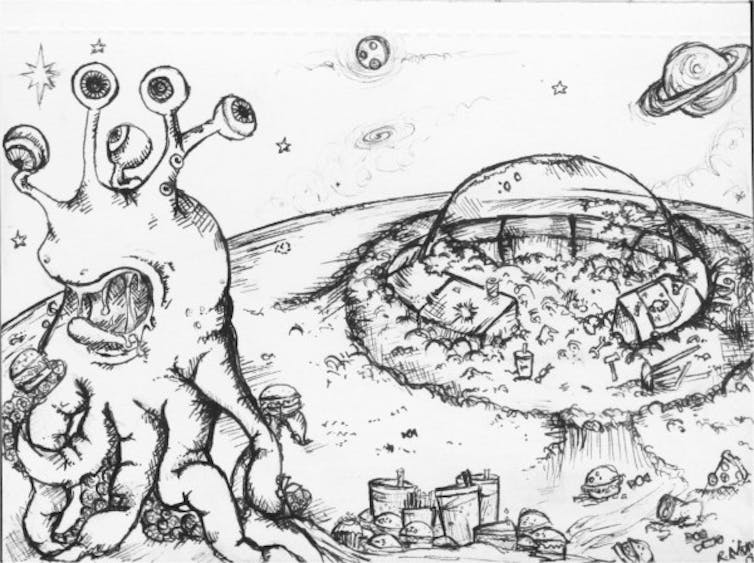

Illustration to a journal article on the intelligence paradox.

The caption reads: Evolution of intelligence will always lead to a drive for environmental utopia.

Hence, many species may well get fat and spend much of their GDP on healthcare.

2014 Nunn et al.

Referencing Oldss experiments, he helped himself to the speculation that hippie drug-use was the prelude tocivilizations wireheading.

Each era has its own anxieties.

So what do we do?

But these are almost certainly not themost pressingrisks facing us.

Andif done right, forms of wireheading could make accessibleuntold vistasof joy, meaning, and value.

We shouldnt forbid ourselves these peaks ahead of weighing everything up.

But there is a real lesson here.

Making adaptive complex systems whether brains, AI, or economies behave safely and well is hard.

Anders works precisely on solvingthis riddle.

In the case of AI, we are laying the foundations of such systems now.

There does, however, remain significant disagreement among expertson timelines, and how pressingthis deadlinemight be.