This is a riddle that artificial intelligence scientists have been debating for decades.

You might guess that the language model will associate it with the second noun in the phrase.

Does AI need a sensory experience?

One of these arguments is theneed for embodiment.

This is a valid argument.

Long before children learn to speak, they develop complicated sensing skills.

They learn to detect people, faces, expressions, objects.

They learn about space, time, and intuitive physics.

They learn to touch and feel objects, smell, hear, and create associations between different sensory inputs.

And they have innate skills that help them navigate the world.

Language builds on top of all this innate and obtained knowledge and the rich sensory experience that we have.

Pink makes me think of a babys cheek, or a gentle southern breeze.

Lilac, which is my teachers favorite color, makes me think of faces I have loved and kissed.

There are two kinds of red for me.

From this, Aguera y Arcas concludes that language can help fill the sensory gap between humans and AI.

As anticlimactic as it sounds, complex sequence learning may be the key that unlocks all the rest.

And hes also right about sequence learning in large language models.

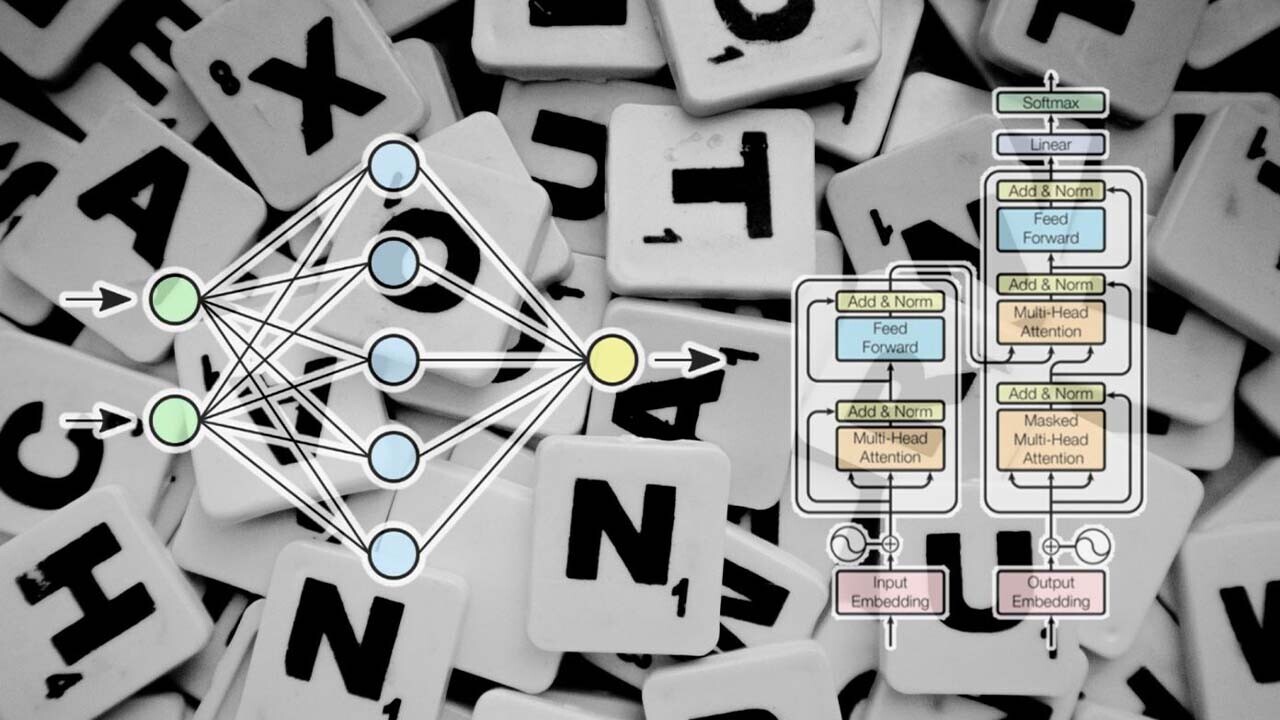

These attention mechanisms help the Transformers handle very large sequences with much less memory requirements than their predecessors.

Are we just a jumble of neurons?

And even if we ever do, some of its mysteries will probably continue to elude us.

And the same can be said of large language models, Aguera y Arcas says.

Such is the source of our belief in our own free will, too, he writes.

I read this article by@blaiseaguerawith great interest.

Last year, Mitchell wrote a paper inAI Magazineonthe struggles of AI to understand situations.

More recently, she wrotean essay in Quanta Magazinethat explores the challenges of measuring understanding in AI.

you might read the original articlehere.