Chinas recent scientific achievements including itsembryo gene-editing researchandhistoric moon landing appear to be surrounded by secrecy.

The global scientific community first learned about its experiments modifying the DNA of human embryosthrough rumors in 2015.

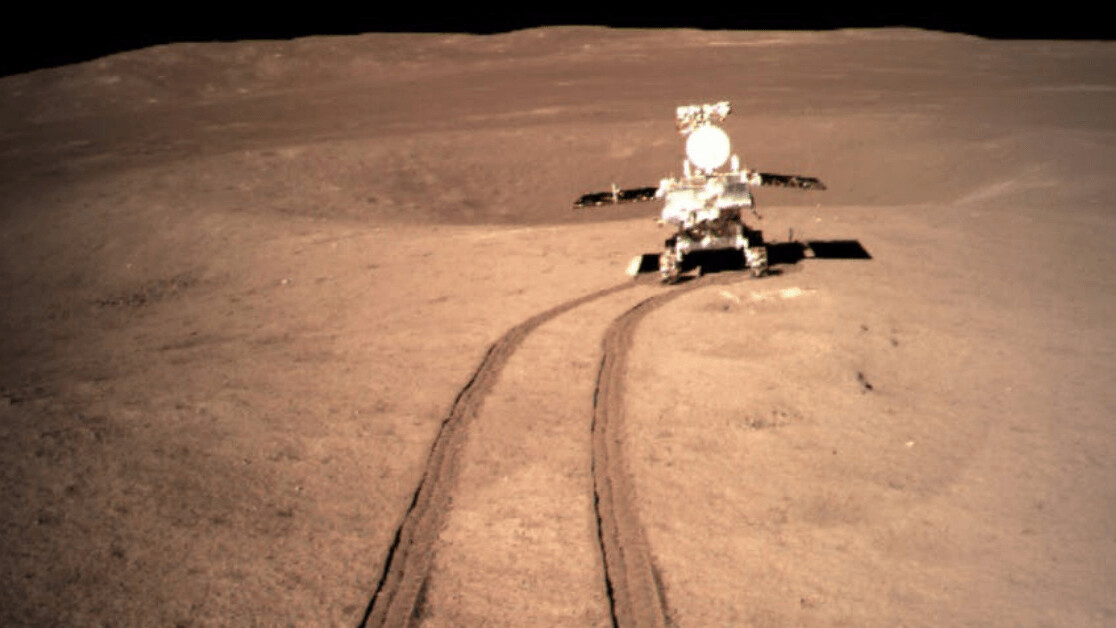

Instead welearned about it through whispersamong journalists and amateur astronomers.

These events demonstrate how little we actually know about whats going on within the Chinese scientific establishment.

They also cast doubt on the accountability of scientific projects carried out in and with China.

Unsurprisingly, this further challenges the global confidence in the countrys researchers.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

The speech set out how to develop China with tangible socioeconomic betterment rather than rhetorical debates.

While that may seem sensible, the approach has led to a number of problems in science governance.

At the institutional level,a pragmatism has taken holdin research oversight.

The primary aim has become to minimize public concerns delivering technological fixes to social problems instead of generating worries.

Unfortunately, though, this doesnt help prevent them from arising in the first place.

Moves that seem tooverturn the prioritiesof doing and talking could be considered politically irresponsible wasting important research opportunities.

Institutions that draw the publics attention may also risk political embarrassment.

For example, great promises of discovery may not materialize.

And ethical concerns can turn out to be nothing.

Conflicted researchers

But why dont the researchers themselves step up and reach out?

For many Western scientists, publicly disclosing possible research harms is seen as a crucial part of good governance.

He Jiankui claimed to have created gene-edited babies.

Thats because they are trotting a thin line of double clientelism.

Communicating with the public also takes skills and training.

There is also little incentive to engage with the media or the public in China.

The stakes, after all, are high.

Chinese authorities have several timesinterferedor even banned technology as a hasty response to a single problematic case.

For example, China developed the worlds first human hybrid embryo in 2001.

This was groundbreaking scientifically, but was also met with international skepticism leading the state toimmediately ban such research.

Change on the horizon?

The secretive culture within Chinese science is therefore not really primarily about active concealment.

There may be reasons for optimism, however.

There is a growing recognition of the value of transparency and public engagement in the country.

These are currently being put forward to high-ranking officials.

But how quickly these commitments will be translated into institutional norms remains to be seen.