Fifteen years ago, physicists atBrookhaven National Laboratorydiscovered something perplexing.

Muons a pop in of subatomic particle were moving in unexpected ways that didnt match theoretical predictions.

Was the theory wrong?

Was the experiment off?

Or, tantalizingly, was this evidence of new physics?

Physicists have been trying to solve this mystery every since.

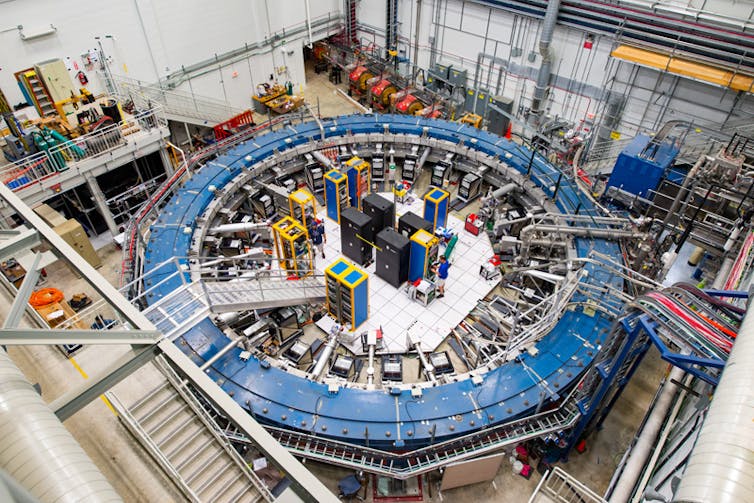

One group fromFermilabtackled the experimental side and on April 7, 2021, released resultsconfirming the original measurement.

But my colleagues and I took a different approach.

40% off TNW Conference!

We used anew methodto calculate how muons interact with magnetic fields.

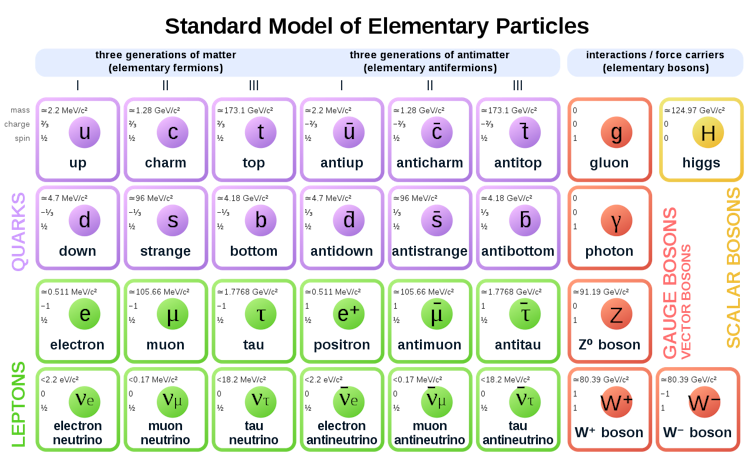

The Standard Model of physics is the most accurate theory of the universe to date.

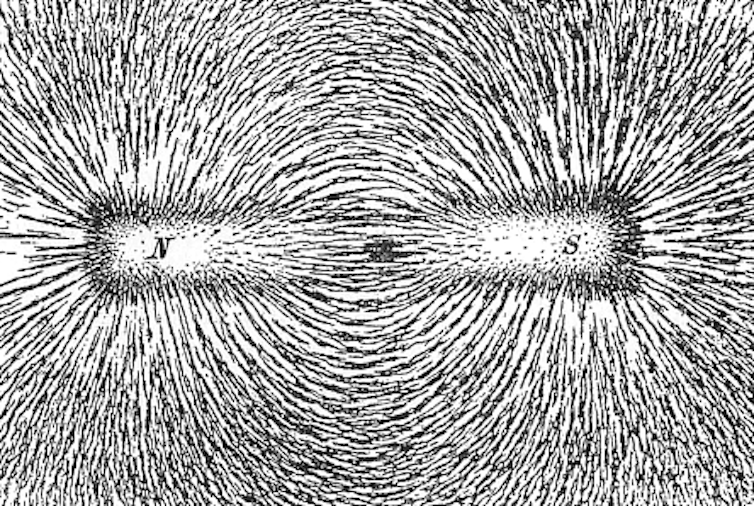

Muons, like electrons, have an electric charge and generate tiny magnetic fields.

The strength and orientation of this magnetic field is called the magnetic moment.

You are probably familiar with the first two: gravity and electromagnetism.

The third is theweak interaction, which is responsible for radioactive decay.

Last is thestrong interaction, the force that holds the protons and neutrons in an atoms nucleus together.

Physicists call this framework minus gravity the Standard Model of particle physics.

The magnetic field of the muon has proven incredibly hard to predict.

In the past, to calculate this effect, physicists used a mixed theoreticalexperimental approach.

Physicists have been using this approach tofurther refine the estimate for decades.

The latest results are from 2020 and produced avery precise estimate.

This calculation of the magnetic moment is what experimental physicists have been testing for decades.

Until April 7, 2021, the most precise experimental result was 15 years old.

By measuring how muons moved and decayed, they were able to directly measure the muons magnetic moment.

So which was it?

So, we decided to give a shot to find a better way to calculate the prediction.

The technique is kind of like making a weather forecast.

Similarly, we placed the strong interaction equation on a space-time grid.

Our team put the strong interaction forces on a grid and looked for the evolution of these fields.

The more planes collecting data, the better the prediction.

They used a more intense muon source that gave them a more precise result.

It matched theold measurement almost perfectly.

The Fermilab results strongly suggest that the experimental measurements are correct.

The new theoretical prediction made by my colleagues and me matches these experimental results.

One mystery remains though: the gap between the original prediction and our new theoretical result.

As always in science, other calculations need to be done to confirm or refute it.