Twitterreports that fewer than 5% of accounts are fakes or spammers, commonly referred to as bots.

Later, Muskput the deal on hold and demanded more proof.

So why are people arguing about the percentage of bot accounts on Twitter?

We brought the concept of the social bot to the foreground andfirst estimatedtheir prevalenceon Twitter in 2017.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

What, exactly, is a bot?

To measure the prevalence of problematic accounts on Twitter, a clear definition of the targets is necessary.

Fake or false accounts are those that impersonate people.

Accounts that mass-produce unsolicited promotional content are defined as spammers.

These types of accounts often overlap.

For instance, you’re free to create a bot that impersonates a human to post spam automatically.

Such an account is simultaneously a bot, a spammer and a fake.

But not every fake account is a bot or a spammer, and vice versa.

Coming up with an estimate without a clear definition only yields misleading results.

Defining and distinguishing account types can also inform proper interventions.

Fake and spam accounts degrade the online environment and violateplatform policy.

Simply banning all bots is not in the best interest of social media users.

This is also the definition Twitter is acting like using.

However, it is unclear what Musk has in mind.

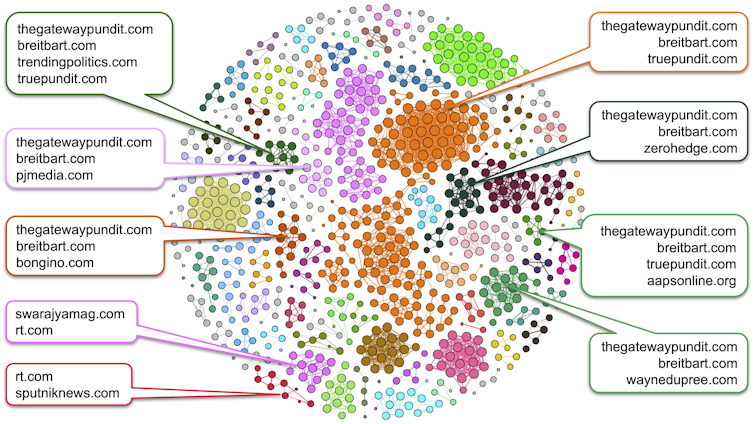

Networks of coordinated accounts spreading COVID-19 information from low-credibility sources on Twitter in 2020.

Thishinders the publics abilityto identify inauthentic accounts.

Inauthentic accounts evolve and develop new tactics to evade detection.

For example, some fake accountsuse AI-generated faces as their profiles.

These faces can be indistinguishable from real ones,even to humans.

Identifying such accounts is hard and requires new technologies.

Yet they are like needles in the haystack of hundreds of millions of daily tweets.

Finally, inauthentic accounts can evade detection by techniques likeswapping handlesor automaticallyposting and deletinglarge volumes of content.

The distinction between inauthentic and genuine accounts gets more and more blurry.

As a result, so-calledcyborg accountsare controlled by both algorithms and humans.

Similarly, spammers sometimes post legitimate content to obscure their activity.

We have observed a broad spectrum of behaviors mixing the characteristics of bots and people.

Estimating the prevalence of inauthentic accounts requires applying a simplistic binary classification: authentic or inauthentic account.

No matter where the line is drawn, mistakes are inevitable.

These issues typically involve many human users.

For instance, the discussion about cryptocurrencies tends to show more bot activity than the discussion about cats.

A meaningful first step would be to acknowledge the complex nature of these issues.

This will help social media platforms and policymakers develop meaningful responses.