The world is being flooded with technology designed to monitor our emotions.

CCTV cameras can track faces through public space, and supposedlydetect criminals before they commit crimes.

Autonomous carswill one day be ableto spot when drivers get road rage, and take control of the wheel.

When Ekman was 14 years old, his mothers depression resulted in her suicide.

His dream of discovery shifted from geography to the uncharted regions of the mind.

Heavily influenced by Freud, Ekman went on to complete a PhD in psychotherapy, studying the depressed.

He was fascinated by nonverbal communication, studying patients body language and hand movements.

By this time, the 1960s, Ekman wasnt the only person to have gone searching.

The acclaimed anthropologist Margaret Mead had already spent years traveling the world, demonstrating that cultures express emotions differently.

Ekman had his doubts.

In her opinion, it wasnt a work that held up in light of more modern research.

Hedefended Darwins initial hunch, because the consensus had flipped.

Innate emotions were in again, and it was Ekmans research that was responsible.

It should be noted that Darwin was far from the first to suggest that emotions were innate.

Nor was Aristotle the only ancient philosopher who thought this way.

It was received wisdom throughout antiquity, persisting well into the late 17th century.

It continues to persist today.

By 1964, Ekman wasstruggling.

Then he could see if there was a link between those facial expressions and inner, universal emotions.

Ekman spent the next eight years alongside Tomkins and another colleague, Wallace Friesen,developing their method.

Those emotions were happiness, anger, sadness, disgust, surprise, and fear.

By chance, another researcher, Austrian ethnologist Irenaus Eibl-Eibesfeldt, independently published similarfindings.

With a jeep and some patience, you could just about drive to the region via a rough track.

Once they reached the Fore, Ekman and Friesen screened their potential test participants.

They found 189 adults and 130 children who fit the bill.

The idea was to use the same photos and stories that the researchers had used everywhere else.

Despite having never seen photos before, the Fore who took part in the experiment caught on quickly.

If the expressions were universal, the stories ought to be linked to just one of the pictures.

The pair published theirresultsin 1971.

Margaret Mead was stunned.

Ekman could have left it there, but his curiosity wouldnt let him.

He wanted to know how Mead and the others could have been so wrong.

He wondered if these expressions, while universal, were influenced by how each specific culture thought someoneoughtto behave.

He ran another experiment.

Ekman secretly filmed the subjects facial expressions.

The people who were alone reacted in the same way, whether they were in Japan or the U.S.

The anthropologists,Ekman suggested, were seeing what their subjects wanted them to see.

Ekman theorized that, despite cultural differences, these universal expressions couldnt be completely suppressed.

He gave them a name: micro expressions.

Ekmans success has led to other discoveries.

All that changed was the timbre of the voice.

Every week, dozens of peer-reviewed papers that build on the categories of basic emotions are published.

Disney even made a movie using five of them as characters:Inside Out.

Understandably, technology companies have put a similar amount of faith in the researchers work.

Examples of this science in action arent just confined to universities and Silicon Valley, either.

Nearly one-fifth of U.S. adultshave an Amazon Echo or equivalent smart speaker, like Google Home.

Alexa also analyzes our voicesto work out our moods.

When you get annoyed, Alexa will calm you down.

When you are happy, she can join you in your joy.

All of this works.

Artificial emotion technology is also being deployed as a crime-fighting tool.

Since 1978, Ekman has been personally teaching people to detect micro expressions.

His work also inspired a TV series, titledLie to Me, on whichhe worked as an adviser.

However, the shows glossy production is misleading about how easy it is to read someones micro expressions.

The TSAs results were usually worse than guesswork.

Where humans fail, technology picks up the slack.

This isnt science fiction the sunglasses of someChinese police officersalready haveface recognition technologybuilt into them.

Programming software is easier when emotions can be categorized and measured.

That may be because emotions arent as simple as Ekman thinks they are.

Almost every paper for the last 50 years has included its own version.

(Even this partial list of different definitions shows how much variation there is.)

This might be because the concept of emotions is a relatively recent one.

Before that, our feelings were subject to a more subtle categorization.

We cant definitively categorize something when its definition has been in flux for so long.

The second, and bigger, problem lies with Ekman and Friesens Papua New Guinea experiment itself.

There were three main issues with this study.

The second issue with the study lies in the use of translation.

What were the single-sentence stories translated to, exactly?

If you do that, you get Google Translate-style results.

Even words in related languages can be difficult to match, too.

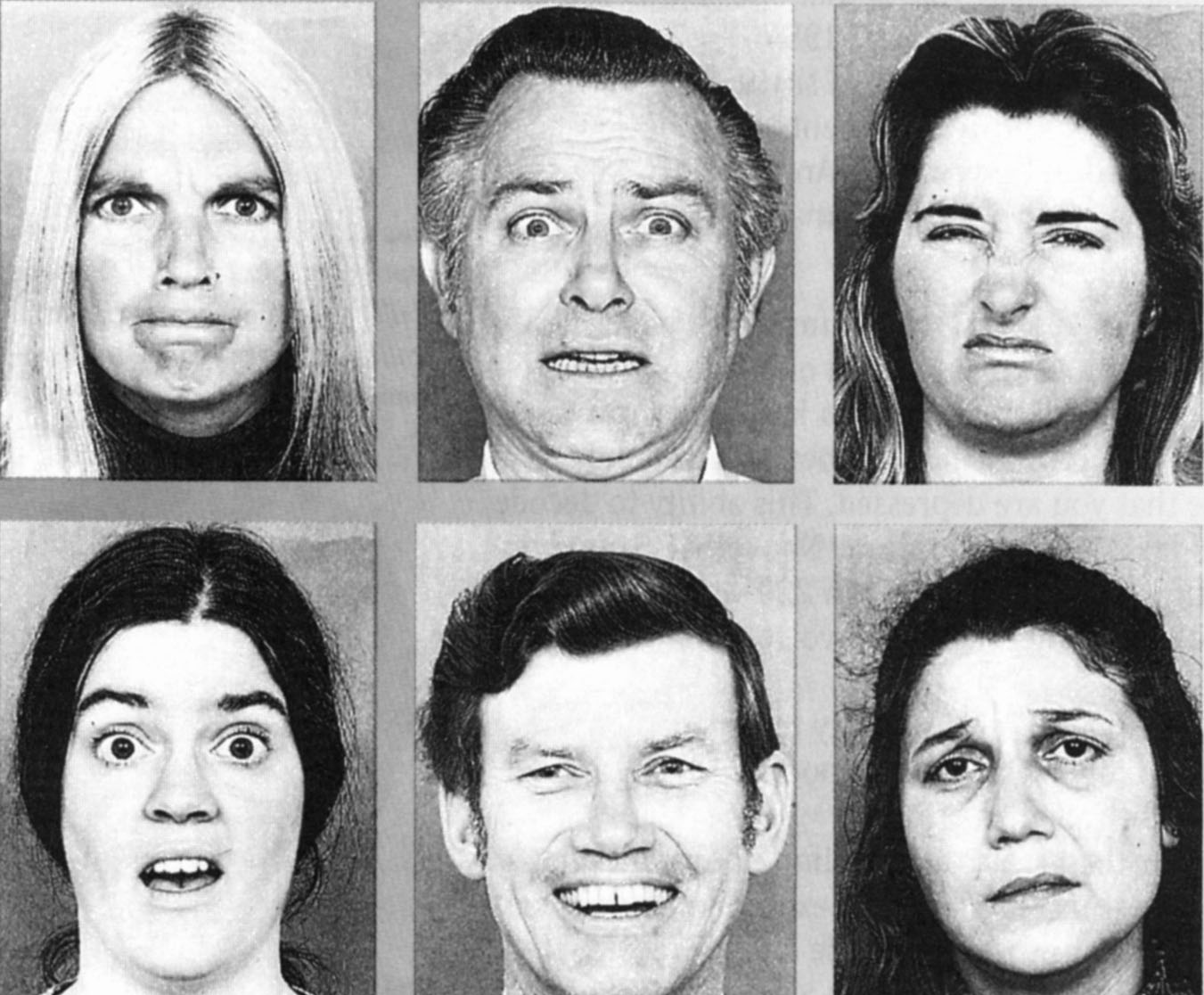

The third issue with the experiment is the faces in the photos.

In real life, facial expressions are rarely as explicit or exaggerated as in Ekmans photographs.

Younger kids dont know if a disgust face is supposed to be disgust or anger, for example.

Furthermore, there are ways of understanding emotions that dont require them to be either universal or simplistic.

For example, thePsychological Construction of Emotion Theoryis gaining significant support in the emotions research community.

Emotions cannot be reduced to just a feeling and a face.

It now looks as though emotions are not universal, after all.

Sadly, this nuance seems not to have filtered down to developers and programmers.

All of these systems have gone wrong.

Deviations from expected, universal expressions of emotion are not to be tolerated.

This article was originally published by Dr Rich Firth-Godbehere onHow We Get to Next.

Read the original articlehere.