In the spring of 2010, physicist Jari Kinaret received an email from the European Commission.

The EUs executive arm was seeking pitches from scientists for ambitious new megaprojects.

Known as flagships, the initiatives would focus on innovations that could transformEuropesscientific and industrial landscape.

Kinaret, a professor atChalmers University of Technologyin Sweden, examined the initial proposals.

I was not very impressed, the 60-year-old tells TNW.

I thought they could find better ideas.

As it happened, Kinaret had an idea of his own: growing graphene.

He decided to submit the topic for consideration.

40% off TNW Conference!

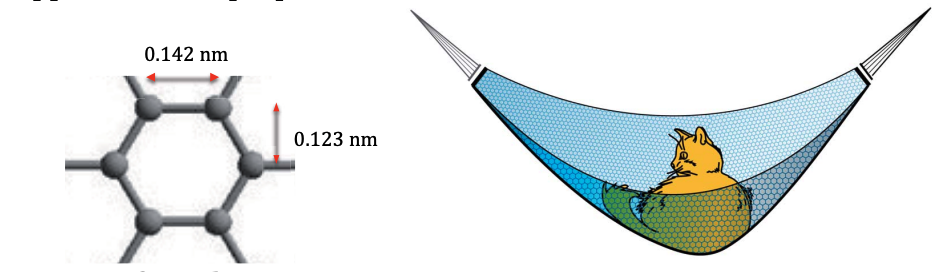

The big breakthrough was sparked by a strikingly simple product: sticky tape.

At one such session, adhesive tape was used to extract tiny flakes from a lump of graphite.

After repeatedly separating the thinnest fragments, they created flakes that were just one atom thick.

The researchers had isolated graphene the first two-dimensional material ever discovered.

The science world was abuzz with excitement.

In 2010, Geim and Novoselov won a Nobel Prize for their discovery.

Kinaret recognized the potential.

Three years later, he was heading an EU drive to take graphene from the lab to the market.

Evolution would be slow but observers were already impatient.

As the Flagships director, Kinaret had to manage such starry-eyed expectations.

At talks, hed frequently refer tothe Gartner hype cycle, a depiction of how newtechnologiesevolve.

The timeline starts with a breakthrough that sparks media excitement.

In graphenes case, reporters were soon claiming the material was set to replace silicon.

Graphene cannot replace silicon, says Kinaret.

Graphene is a semi-metal; its not a semiconductor.

Graphene appears to have exited this perilous period, partly thanks to the EUs long-term commitment.

The backers that remain tend to be more practical and persistent.

Now, their target is mainstream adoption.

Thats something we promised and delivered.

Initially, many commercial partners were frugal with their investments.

Nokia, for instance, would have to collaborate with Ericsson.

One dimension of trust that people needed was to trust this is for real, says Kinaret.

The other is that participants needed to trust each other.

The Flagships current membership suggests that trust has now been secured.

The proportion of companies has grown from 15% to roughly 50% today.

The other half are either research organizations or universities.

Kinaret describes the growth of industrial engagement as the Flagships key development.

Thats something that we promised, and its something we have delivered, he says.

From lab to fab

Around 100 products have emerged from the Graphene Flagship.

The vast majority are business-to-business technologies, such asthermal coating for racing carsand eco-friendlypackaging for electronic devices.

Consumers products have been slower to commercialize.

Kinaret spotlights a few of his favorites.

The graphene detectors could cost about $1 each.

That would be a total game changer in that business.

Another highlight for Kinaret isInbrain Neuroelectronics.

The startup is developing graphene-based implants that can monitor brain signals and treat neurological disorders.

The devices could eventually stimulate the brain to control tremors resulting from Parkinsons disease.

Traditional electrodes can achieve this, but theyre far stiffer than highly-flexible graphene.

The brain is like a lump of jelly it keeps moving around, says Kinaret.

If you put a stiff electrode there, it results in scar formation.

Kinaret is also excited about the prospects for fundamental science.

In 2018, Graphene Flagship partners revealed that over 2,000 materials can exist in a 2D form.

Not all of them are stable, but a number of them are the focus of active research.

you’re free to make superconducting materials.

Some researchers are exploring what can be achieved by stacking the substances in multi-layers.

This misalignment angle is a very important new parameter, says Kinaret.

But it offers interesting possibilities for thefuture.

Mission accomplished?

Kinaret is proud of the Flagships achievements.

He believes the initiative has surpassed its targets by significant margins.

The data appears to support his claims.

The European Commission aims to turn every 10 million thats invested into one patent utility.

The Flagship, says Kinaret, has more than 10 times that requirement.

The targets for scientific publications, he adds, have been surpassed by a similar factor.

There are still challenges to overcome.

Nonetheless, Kinaret reminds the team they should remain positive.

Engineers are typically short-term optimists and long-term pessimists, he says.

In the future, Kinaret expects Europe to become a graphene powerhouse.

The Flagship has given the continent a head start over the US in the race toward the mainstream.

He admits, however, that laypeople still ask what graphene is and can do.

If we get to a situation where a surprised what?

has been replaced by so what?

because its become ubiquitous or mainstream… then well have made it.

Story byThomas Macaulay

Thomas is the managing editor of TNW.

He leads our coverage of European tech and oversees our talented team of writers.

Away from work, he e(show all)Thomas is the managing editor of TNW.

He leads our coverage of European tech and oversees our talented team of writers.

Away from work, he enjoys playing chess (badly) and the guitar (even worse).