Stakhanov shattered this norm by a staggering 1,400%.

But the sheer quantity involved was not the whole story.

It was Stakhanovs achievement as an individual that became the most meaningful aspect of this episode.

That trend still holds sway in the workplaces of today what are human resources, after all?

Management language is replete with the same rhetoric used in the 1930s by the Communist Party.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

But all this positive talk comes at a price.

The speed with which this language grew and spread was remarkable.

This is no less than the very language of the modern sense of self.

And so it cannot fail to be effective.

Focusing on the self gives management unprecedented cultural power.

It intensifies work in ways which are nearly impossible to resist.

Who would be able to refuse the invitation to express themselves and their presumed potential or talents?

They have all become the attributes management systems now hail as the qualities of ideal human resources.

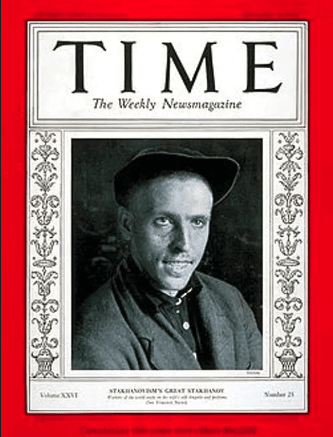

The superhero worker

So, why does the specter of this long-forgotten miner still haunt our imaginations?

Once the Communist Party realized the potential of Stakhanovs achievement, Stakhanovism took off rapidly.

By the autumn of 1935, equivalents of Stakhanov emerged in every sector of industrial production.

The party wanted to create an increasingly formalized elite representing the human qualities of a superhero worker.

And so the Stakhanovites became central characters in Soviet Communist propaganda.

Soviet propaganda seized the moment.

It turns out that such a story was sorely needed.

The Soviet economy was not performing well.

The first aimed to inject the latest technology in key areas, especially industrial machine building.

Its official Communist Party slogan wasTechnology Decides Everything.

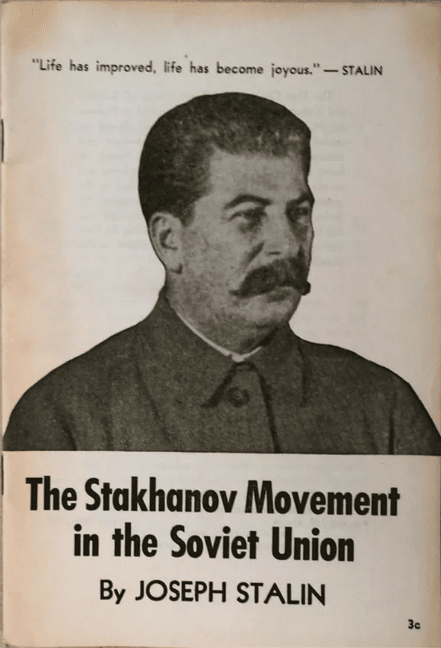

TheSecond Five-Year Plan(1933-1937) was going to have a new focus:Personnel Decides Everything.

But not just any personnel.

On May 4, 1935, Stalin had already delivered anaddressentitledCadres [Personnel] Decide Everything.

So the new plan needed figures like Stakhanov.

On November 17, 1935, Stalin provided a definitive explanation of Stakhanovism.

Surpassing them because these standards have already become antiquated for our day, for our new people.

In the ensuing propaganda, Stakhanov became a symbol burdened with meanings.

Ancestral hero, powerful, raw, and unstoppable.

Stakhanovism was the vision of a new humanity.

The possibilities are endless

The Stakhanovites celebrity status offered enormous ideological opportunities.

It allowed the rise of production quotas.

Yet this rise had to remain moderate, otherwise Stakhanovites could not be maintained as an elite.

After all, how many high-performers can there be at any one time?

Welchs argument was, however, always flawed.

Any forced distribution system inextricably leads to exclusion and marginalization of those who fall in the lower categories.

Far from humane, these systems are always, inherently, threatening and ruthless.

Stakhanov fitted perfectly this ideal.

Western culture has been telling itself the same ever since the possibilities are endless.

On one side it said: The possibilities are endless.

How far will you take it?

But are these serious propositions, or just ironic tropes?

Since the 1980s, management vocabularies have grown almost incessantly in this respect.

It is in this light that we have to show ourselves as worthy members of corporate cultures.

Pursuing endless possibilities becomes central to our everyday working lives.

Stakhanovisms essence was a new form of individuality, of self-involvement in work.

Stakhanovism has become a movement of the individual soul.

But what does an office worker actually produce and what do Stakhanovites look like today?

The shows characters become almost instantly ruthless neo-Stakhanovites.

It was not what they did but how they appeared that mattered.

The dangers of failing to appear extraordinary, talented, or creative were significant.

The series showed how working life descends into unending personal, private, and public struggles.

In them, every character loses a sense of direction and personal integrity.

Trust disappears and their very sense of self increasingly dissolves.

Normal days of work, normal shifts, no longer exist.

Workers have to perform endlessly, gesturing so that they look committed, passionate, and creative.

These things are compulsory if employees are to retain some legitimacy in the workplace.

Nobody wants to fall out of the Stakhanovite society of hyper-performing top talents.

Performance appraisals that may lead to dismissal are a scary prospect.

And this is the case both in the series and in real life.

The last episode ofIndustryculminates in half the remaining graduates getting sacked following an operation called Reduction In Force.

This idea is taken further in an episode ofBlack Mirror.

What if everyone around us becomes our judge?

Management systems focusing onindividual personalityare now combining with the latest technologies to becomepermanent.

The Circle, by Dave Eggers, is perhaps the most nuanced exploration of the world of 21st-century Stakhanovism.

But who can maintain this kind of hyper-performative life?

Is it even possible to be excellent, extraordinary, creative, and innovative all day long?

How long can a shift of performative work be anyway?

The answer turns out not to be fictional at all.

Then in 2012, wepublished our reviewwhich signaled the dangers of the hyper-performative mold promoted in such publications.

A year later, this sense of danger became real in Erhardts case.

Stakhanov died after a stroke in Donbass, in eastern Ukraine, in 1977.

A city in the region is named after him.

The legacy of his achievement or at least the propaganda that perpetuated it lives on.

But the truth is that people do have limits.

They do now, just as they did in the USSR in the 1930s.

Possibilities are not infinite.

Working towards goals of endless performance, growth and personal potential is simply not possible.

The danger is that we will not be able to sustain this rhythm.