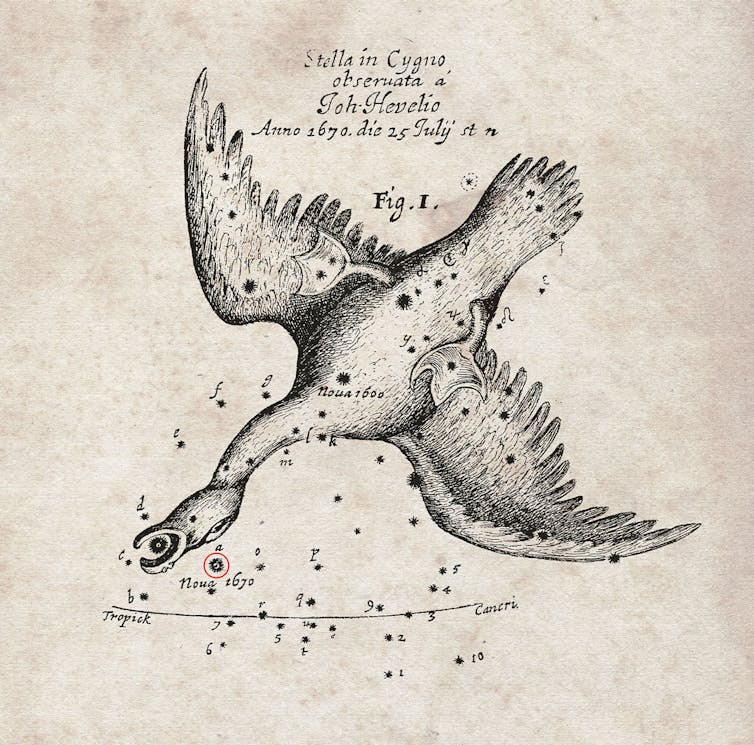

A bright new star appeared in the sky in June, 1670.

Over the next few months, it slowly faded to invisibility.

Again it faded, and by the end of the summer it was gone.

Then in 1672, it put in a third appearance, now only barely visible to the naked eye.

After a few months it was gone again and hasnt been seen since.

This has always seemed to be an odd event.

For centuries, astronomers regarded it as theoldest known nova a key in of star explosion.

But this explanation became untenable in the 20th century.

40% off TNW Conference!

Stars can also explode as supernovae, following an implosion of their core.

However, we know now that neither would give the kind of repeated appearance seen in this event.

So what was it?

Our new research, published in theMonthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, offers a whole new explanation.

This proved that something had indeed happened here.

Astronomers later noted that the nebula was expanding, and that the expansion had started around 300 years ago.

But the star itself couldnt be seen.

These require very high temperatures to form.

Whatever happened, this had been a high-energy event.

New observations

We observed the location of the star withALMA observatory in Chile.

This spectacular-looking telescope uses 64 separate dishes, and observes in the microwave region of light.

It is particularly good at detecting radiation from molecules in space.

Such hourglass lobes indicate the presence of jets coming from the centre, which blow out the opposing bubbles.

But the hourglasses are at slightly different angles.

This suggests that the originating structure was spinning, and this requires a protracted process.

Whatever happened, it was not just a single explosion.

The ejection must have taken some time.

The alternative to a stellar explosion is a collision between two stars.

These are rare events which have caught much attention in recent years.

In 2008, a collisionwas caught near the centre of our galaxy.

The colliding stars circled each other closely, before finally merging.

CK Vul could be the result of a merger between two normal stars.

But this didnt seem to fit.

Luckily, though, there is a complete zoo of possible collisions, as stars come in many types.

They are 10 to 80 times heavier than Jupiter.

Brown dwarfs are probably quite common, but they are hard to find because they are so faint.

A collision between a white dwarf and a brown dwarf would be spectacular.

The brown dwarf would be shredded by the much heavier and denser white dwarf.

The rest of the brown dwarf would be swept up in the debris from the outburst.

The remaining dust shells may also have contributed, making it opaque to visible light.

Is this what actually happened?

We have made a plausible model but further tests would be required to produce conclusive evidence.

For example, would this collision provide the right conditions to form radioactive aluminium?

Upcoming observations could look at the details of the innermost region of the hourglass structure to find out.

Our discovery represents the first ever detection of a collision between a white and a brown dwarf.

Once confirmed, we can use it to look for other events like it.

Astronomy is an adventure: a beautiful mix of physics and discovery.

We are still learning.

This article is republished fromThe ConversationbyAlbert Zijlstra, Professor of Astrophysics,University of Manchesterunder a Creative Commons license.