Graphenes spec sheet reads like a superheros profile.

When the sheet of carbon wasfirst isolated in 2004 at Manchester University, the breakthrough rocked the scientific world.

Countless applications for the miracle substance were envisioned, from storing solar power to stitching batteries into bodies.

At the EU, plans to capitalize on the materials promise were drawn up.

In 2013, the bloc launched the Graphene Flagship, an initiative to commercialize the material.

The early graphene gold rush, however, didnt immediately lead to riches.

But a promising sector is slowly emerging on the continent.

Among Europes torchbearers isInbrain Neuroelectrics.

Founded in 2019, the Graphene Flagship spinoff uses the material todevelop neural interfaces.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

Inbrains landmark trial will assess the suitability of graphene-based implants for treating brain conditions.

If proven safe and effective, the material could bring numerous advantages to neural interfaces.

We can also see the biomarkers at least 10 times better.

This combination enables Inbrain to decode detailed biomarkers from neural activity, while minimizing power consumption and ensuring stability.

In time, the devices could produce personalized, therapeutic treatments for neurological disorders.

These features differentiate graphene from more commonly-used metals, such as platinum-iridium.

Miniaturizing these materials can impair their durability and electrical impedance.

We can also see the biomarkers at least 10 times better than with platinum-iridium, says Aguilar.

Graphene also gives Inbrain an edge over Neuralink, Elon Musksbrain chipstartup.

Neuralink devices use a material called Pedot, which degrades far more quickly than graphene.

These qualities, however, are no guarantee of commercial success.

Despite its unique properties, bringing graphene to market remains a challenge.

Leaving the lab

The Graphene Flagship is not without its critics.

Pundits have questioned the value of the EUs immense investment, and the slow process of developing real-world applications.

The speed, however, should not be too surprising.

Taking a novel material from discovery to commercialization frequently takes decades.

In graphenes development, arguably the biggest current problem is providing cost-effective production.

One of the most auspicious solutions was pioneered byParagraf, a company that commercializes graphene-based electronics.

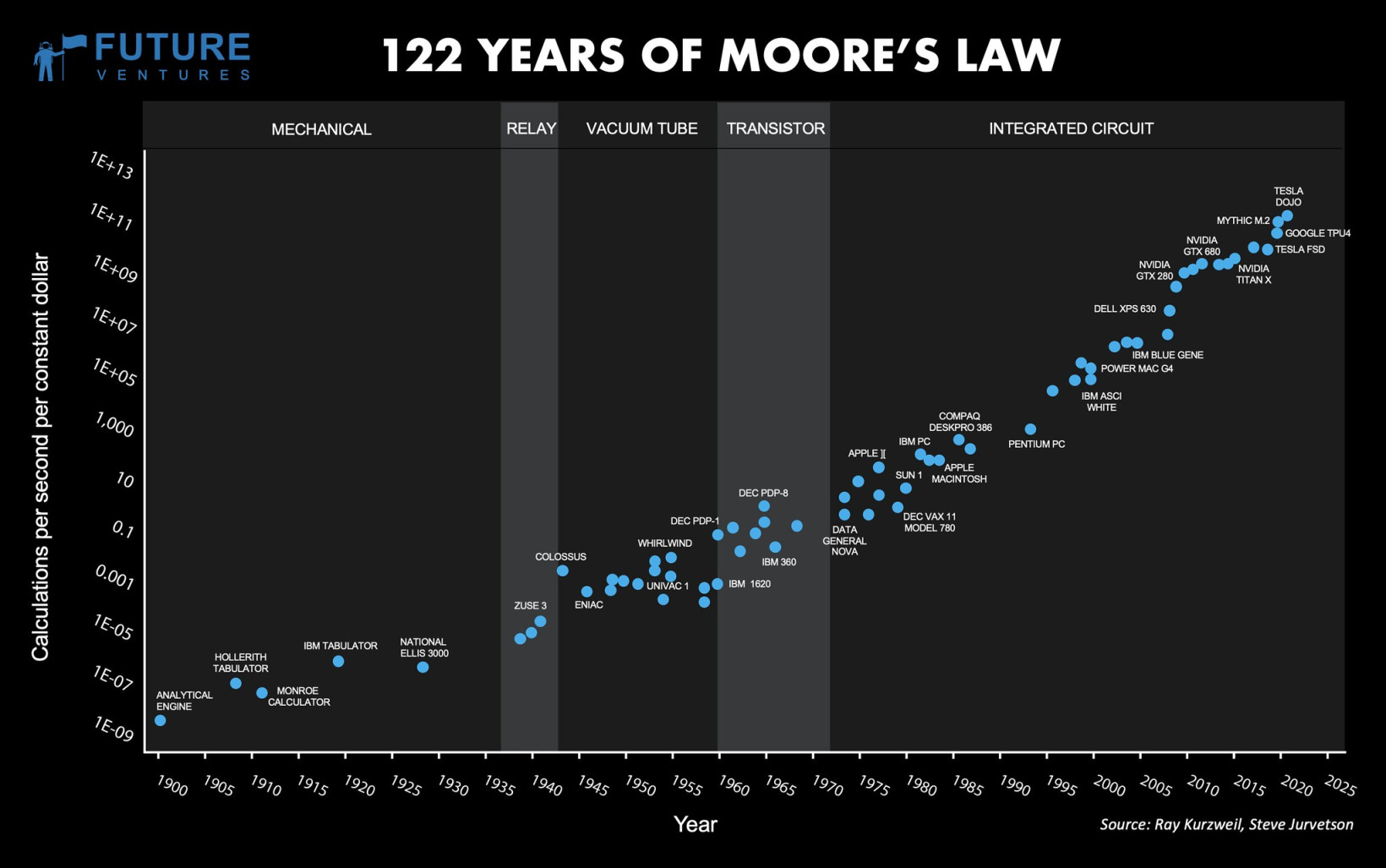

Graphene can reboot Moores Law.

Paragraf claims to be the first company to offer scalable manufacturing of graphene-based electronic devices.

Paragraf has actually done that.

Paragraf has made graphene an industry-ready solution.

Paragrafs graphene-based sensors can power an array of applications, from quantum computers to rapid COVID- 19 tests.

Early customers include Rolls-Royce and the Cern research lab.

Wilson is bullish about graphenes benefits to computer chips.

Graphene has the promise of rebooting Moores Law.

This potential, however, is being inhibited by a global semiconductor shortage.

They have also raised concerns about the post-Brexit talent pipeline and the inadequate support for university spin-offs.

Whichever way they go, the key is clarity.

The EU, meanwhile, could greenlight its European Chips Actby the end of the year.

That would be a boost to Inbrains tech, which also relies on semiconductors.

For Aguilar, the companys CEO, the EUs biggest shortcomings are insufficient venture capital and infrastructure support.

Despite the challenges, optimism about graphenes future is growing once again.

Wilson believes that a revolution in advanced materials electronics has begun.

But Europe still needs to cement its place in the vanguard.

Production challenges, funding gaps, andcompetition from China and the USremain major obstacles to the EUs ambitions.

The bloc still has to find mass markets for the wonder material.

Story byThomas Macaulay

Thomas is the managing editor of TNW.

He leads our coverage of European tech and oversees our talented team of writers.

Away from work, he e(show all)Thomas is the managing editor of TNW.

He leads our coverage of European tech and oversees our talented team of writers.

Away from work, he enjoys playing chess (badly) and the guitar (even worse).