Youve probably seen images of scientists peering down a microscope, looking at objects invisible to the naked eye.

Indeed, microscopes are indispensable to our understanding of life.

They are just as indispensable to biotechnology and medicine, for instance in our response to diseases such asCOVID-19.

Creating a damage-evading microscope like ours is a long-awaited milestone oninternational quantum technology roadmaps.

It represents a first step into an exciting new era for microscopy, and for sensing technologies more broadly.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

A cell getting uncomfortable and then dying under a laser microscope.

Microscopes have a long history.

They are thought to have been first invented by the Dutch lens-makerZacharias Janssenaround the turn of the seventeenth century.

He may have used them to counterfeit coins.

The more recent invention of lasers provided an intense new kind of light.

This made a whole new approach to microscopy possible.

However, laser microscopes face a major problem.

The very quality that makes them successful their intensity is also their Achilles heel.

The best laser microscopes use light billions of times brighter than sunlight on Earth.

As you might imagine, this could cause serious sunburn!

In a laser microscope, biological samples can become sick or perish in seconds.

Spooky action at a distance provides the solution

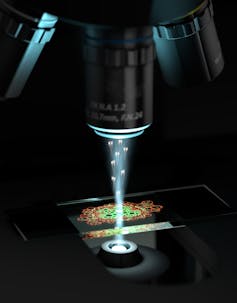

Our microscope evades this problem.

It uses a property called quantum entanglement, which Albert Einstein described as spooky action at a distance.

Our microscope uses pairs of quantum correlated photons to achieve clarity that would be impossible with regular light sources.

Other microscopes need to increase the laser intensity to improve the clarity of images.

By reducing noise, ours is able to improve the clarity without doing this.

Alternatively, we can use a less intense laser to produce the same microscope performance.

A key challenge was to produce quantum entanglement that was bright enough for a laser microscope.

This produced entanglement that was 1,000 billion times brighter than has previously been used in imaging.

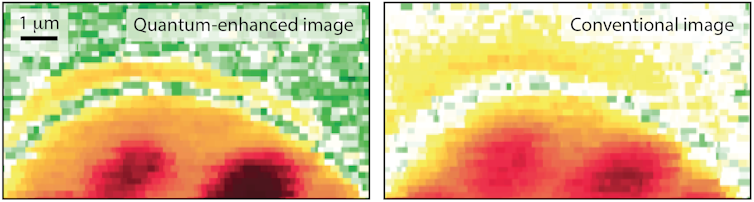

We used the microscope to image the vibrations of molecules within a living cell.

This allowed us to see detailed structure that would have been invisible using traditional approaches.

The improvement can be seen in the images below.

These images, taken with our microscope, show molecular vibrations within a portion of a yeast cell.

The left image uses quantum entanglement, while the right image uses conventional laser light.

Example of quantum enhancement possible with our microscope.

Quantum entanglement underpins many of these applications.

A key challenge for quantum technology researchers is to show that it offers absolute advantages over current methods.

Entanglement is alreadyusedby financial institutions and government agencies to communicate with guaranteed security.

Quantum sensors are the last piece of this puzzle.

About a year ago quantum entanglement was installed inkilometre-scale gravitational wave observatories.

This allows scientists to detect massive objects further away in space.