How well we distribute and administer a COVID-19 vaccine will have massive health, social, and economic ramifications.

So attention is turning to vaccine supply chains and logistics.

Designing how best to vaccinate billions of people worldwide is complex.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

We assumed most vaccine distribution would be by road and enoughrefrigerated vehicleswould be available.

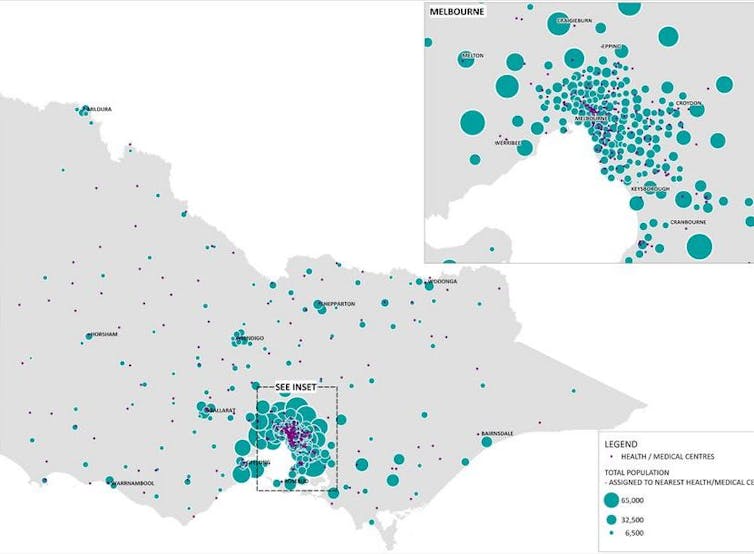

These people are not uniformly distributed around the state, affecting vaccine distribution logistics.

We then tested different scenarios to see how long vaccination would take.

Our research shows we need three key factors for success.

By capacity, we mean the maximum number of vaccine doses each medical center can administer.

This time frame or target horizon is the total number of days to vaccinate the population of Victoria.

This assumes one shot per person and adequate vaccines are available.

A limited supply or a disruption to supplies might increase the administration period beyond 60 days.

This could be by using mobile vaccination units or hiring extra staff.

This allows medical centers short on vaccines to obtain doses from the nearest medical centers with extra supply.

Transshipment is also crucial when it comes to vaccinating the most vulnerable people.

Transshipment also allows us to transfer vaccines from areas with less exposure to areas of higher exposure.

And it allows vaccines to reach remote areas.

However, transshipment places an extra burden on road transport networks.

This seemingly minor detail had a significant effect on the overall period of vaccine administration.

We considered pack sizes that contain 5, 12, 20, 30, and 50 vaccines.

A larger pack size significantly increases the need for transshipment between medical centers.

We suggest governmental agencies carefully evaluate vaccine pack size when contracting and negotiating with vaccine manufacturers.