But is the research a win for electric vehicle manufacturing or a starting point for really getting stuff done?

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

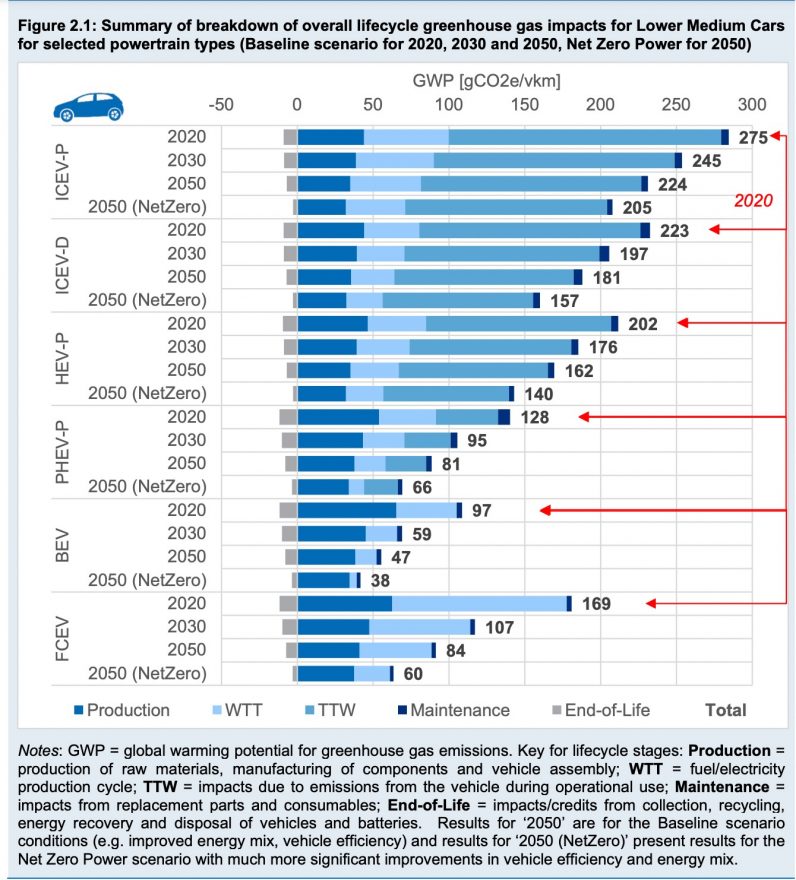

Production emissions for EVs were around 50% higher than petrol cars in 2020.

This is mainly due to the batteries which made up 67% of total estimated lifecycle GHG emissions.

However, vehicle and battery recycling and potential second-life applications could offset these emissions.

The research asserts that, by 2050, BEV production emissions could reach close to parity with conventional vehicles.

This is helped by the decarbonization of the UK electricity grid.

By 2050, these savings could increase to a whopping 81%.

Specifically, lifecycle GHG reductions from FCEVs are around 60-70% higher than for an equivalent EV.

This is because of the lower overall efficiency of the full energy chain for hydrogen produced from electricity.

But analysts still found that FCEVs shine in the heavy vehicle category.

Overall, its a long way from the promises of those betting on hydrogen.

And automakers have their own goals.

For example,Volvoplans to stop manufacturing ICEs altogether by 2030.

Then, theres the health of the UK energy grid to manage all theEVcharging needs.

On top of this, we need to discuss the materials used in electric vehicle batteries.

There are also abundant efforts to reduce the use ofethically and environmentally problematicmaterials likelithiumand cobalt.

Therefore, any commitments in the auto industry need to be backed up with timelines and consequences for non-compliance.

So, its likely that cars on the roads will look vastly different by 2030 and even 2050.

The vast majority will, of course, be EVs.

But the biggest win would be lower rates of car manufacturing and significant investment into more sustainable people-carrying.

For example, micromobilty and public transport.

Then, well really have something to write about.

Story byCate Lawrence

Cate Lawrence is an Australian tech journo living in Berlin.