Much of the legal foundation for the units work is rooted in a 22-year-old comparison of bluejeans.

40% off TNW Conference!

It said image examiners have never relied on those methods because they have been demonstrated to be unreliable.

But the unitsarticlesandpresentationsonphoto comparisonshow its practices mirror those used in the studies.

The bureau did not address examiners inaccurate testimony and other questionable practices.

Their conclusions are, basically, my hunch is that X is a match for Y, he said.

Only they dont say hunch.

Some of it is very good, like DNA.

Some of it is pretty good, like fingerprinting.

And some of it is not good at all.

Details on FBI caseloads and testimony are not readily available to the public.

Few criminal convictions, though, make it to an appeal.

Even DNA analysis can beswayed by bias, Dror said.

But pattern-matching fields like image analysis are especially vulnerable.

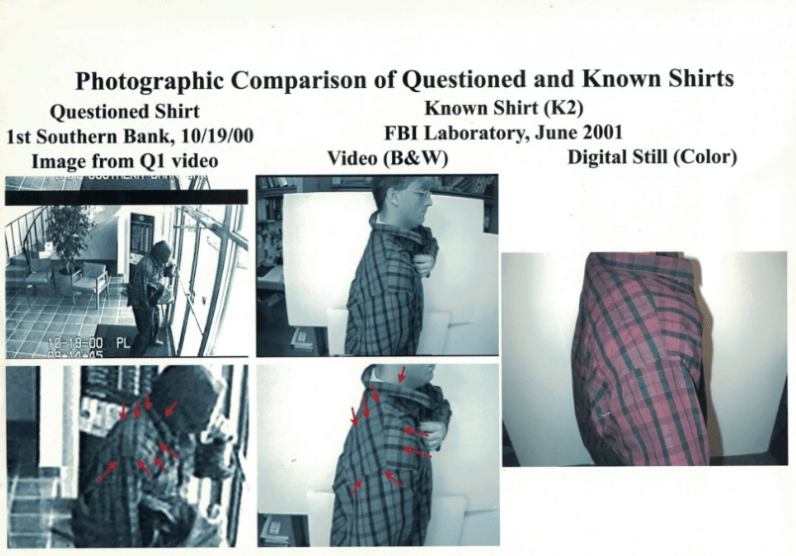

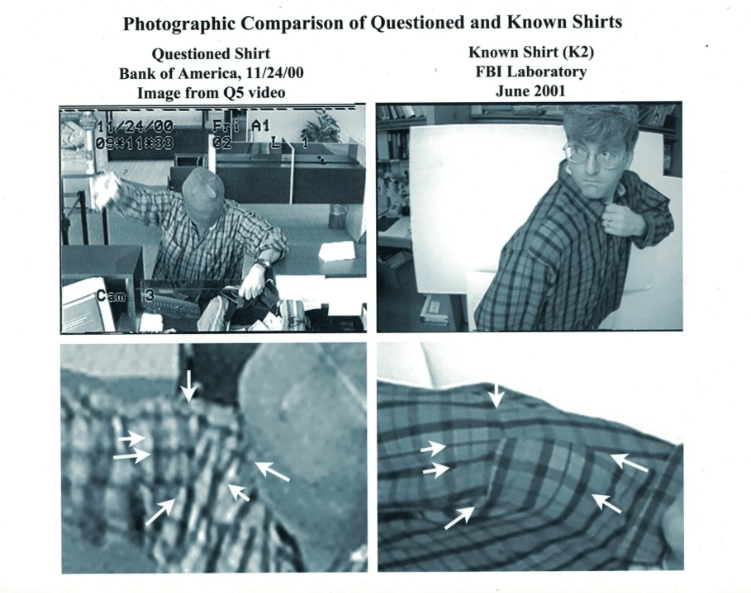

A bank robbery trial 16 years ago was a watershed for such testimony.

Prosecutors charged an ex-convict with robbing a string of banks across South Florida over two years.

The examiner said he matched lines in the shirt patterns at eight points along the seams.

Witnesses had seen a burgundy-colored sedan similar to McKreiths Mercedes-Benz outside a majority of the robberies.

(He said he borrowed money from his parents.)

The statistics were also preposterous, seven statisticians and independent forensic scientists told ProPublica.

No one has studied the alignment of lines on mens button-down shirts.

She said Vorder Bruegges statements are brazen.

Research has bolstered some of the image units practices.

In both, participants couldnt consistently mark the features to use in an analysis.

Those studies found alarming inconsistency.

Its not a reliable measure.

The FBI response to ProPublica said the image units own methods differ from those in the studies.

But the unitspublished descriptions of its practicesshow they are effectively the same as the ones tested by researchers.

Image examiners testified about conclusions based on these methods as recently as last year.

But image analysis has otherwise drawn little scrutiny.

Such deficiencies rarely matter in court.

Few defense lawyers receive training in science or statistics, leaving them ill-suited to dispute expert witnesses.

Whitehurst told the court his lab colleagues had produced inaccurate reports in the case.

He had complained within the lab for years about unqualified explosives examiners and shoddy scientific practices.

The FBI mostly dismissed the concerns and, Whitehurst said, reassigned him to a different unit as retaliation.

So he went public on the stand and to the press.

The Justice Departments Office of the Inspector General was already investigating Whitehursts allegations.

We found, however, significant instances of testimonial errors, substandard analytical work, and deficient practices.

The lab already knew about a second problem.

The in-house review looked at examiner Michael P. Malones lab work and sworn statements in more than 250 cases.

It found Malone routinely misrepresented his results as valid and his error rate as less than 1 percent.

Microscopic hair comparisons were particularly vulnerable to debunking because follicles contain genetic material.

For decades, examiners told jurors that crime scene hairs came from defendants.

DNA analysis later proved the hairs did not in dozens of cases.

(The FBI replaced microscopic hair comparisons with DNA in 1999.)

Prompted by the Posts investigation, the Justice Department finishedan expansive reviewof hair comparison testimony.

Hair examiners matched defendants to follicles in 268 trials; all but 11 contained scientific error.

They were more conservative in their written lab reports, about half of which included a misstatement.

Like other forensic science reckonings, the public disclosure came years after the FBI stopped relying on the method.

Another unit at the FBI Lab had for decades matched bullets by their chemical compositions.

The bureau had no science to back its claims.

Thereport by researchersin 2004 said the examiners testimony went further than the chemical analysis allowed.

Further, one bullet could match anywhere from 12,000 to 35 million other bullets.

FBI officials discontinued lead analysis a year later.

The FBI Lab is a fixer, Whitehurst said in an interview last year.

Examiners have many incentives to find evidence that helps a conviction, he said.

In 2009, the National Academies of Sciences published a wide-ranging evaluation of the forensic sciences and their deficiencies.

It recommended crime labs be moved out of the police and prosecuting agencies that have always run them.

The Justice Department never publicly considered separating Quantico from the FBI.

It also called on the FBI to dramatically increase spending on studies to prove its methods.

U.S. Department of Justice officialsrejected most of the advisers conclusions.

Federal law enforcement has doubled down on unproven forensic science.

The report makes broad, unsupported assertions regarding science and forensic science practice.

The FBI response to a 2016 report by a presidential advisory panel criticizing pattern evidence.

Sept. 20, 2016.

The department alsostopped its internal review of testimonyfrom FBI pattern evidence units.

In a law review article last year, two high-rankingFBI Lab scientists dismissedvalidation concerns as uninformed.

Quantico is, indeed, accredited.

But the lab has never proven photo analysis is reliable.

It has increasingly done the opposite.

Methods are taught through apprenticeships, with new examiners doing casework alongside lab veterans.

After Congress passed a law in 1968 requiring banks to have security equipment, most banks installed surveillance cameras.

Pictures flooded the bureau as evidence.

No scientific background or advanced degrees were required.

Photographs were fuzzy and poorly lit, especially those from bank cameras.

Robbers often wore masks.

When a criminals face was obscured, they looked at the ears, shirts, pants and shoes.

Fingerprint examiners focus only on the swirls and deltas on human fingertips.

Hair fiber examiners only analyzed hairs and fibers.

Still, the unit requires examiners to study photography and little else before working on criminal cases.

There werent even formal courses on photo comparison until 2005, court records show.

Judges long accepted examiners testimony as expert opinion without much debate.

Agents were experts because they worked at the FBI Lab.

Then, in June 1993, the Supreme Court transformed the law around scientific evidence.

None of the pattern evidence fields met that standard.

The Daubert decision posed an existential threat to many forensic sciences.

A month later, the image unit dodged a legal mine set by Daubert.

Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments on a bank robbery conviction in Southern California.

Ascientist for the defensetestified that clothing comparison was unproven.

The appellate court upheld DAmbrosios conviction without weighing the scientific merit.

Circuit Court of Appeals Unpublished Deposition 9 F.3d 1554)

Clothes comparison escaped without damage.

But all of the units methods seemed vulnerable to challenge.

The image unit was filled with former field agents and lab technicians, few of whom held advanced degrees.

None had a background in research or academic publishing.

Those studies can be complicated to organize and are risky.

What if the results disprove what examiners have said under oath for decades?

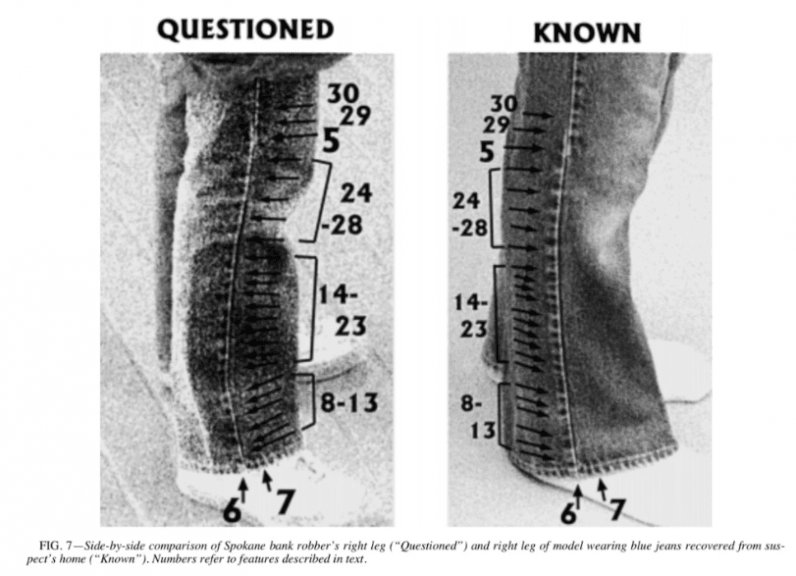

A similar attack followed three months later at a Planned Parenthood clinic in Spokane and the same bank branch.

The bombs caused building damage but no injuries.

Surveillance video showed three men in ski masks, heavy jackets and denim jeans.

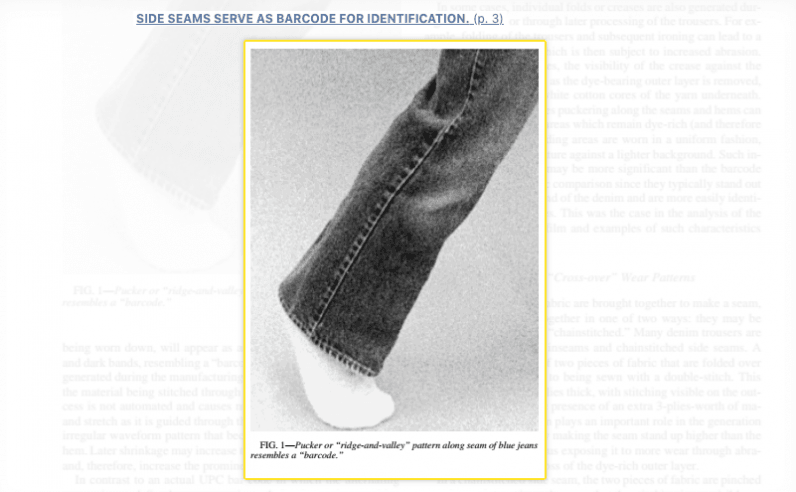

Back at the lab, Vorder Bruegge compared the pants against still images from bank video.

The seized pants wereJ.C.

Penney plain pocket jeans, which the department store chain marketed asnearly indistinguishablefrom more expensive Levis 501 jeans.

Atsix points in the article, he acknowledged the method was not validated.

It helpedan array of methodsmeet the Daubert standard and become admissible scientific evidence in criminal trials.

Leading forensic scientists, statisticians and clothes manufacturing experts reviewed Vorder Bruegges article at ProPublicas request.

They said the FBI examiners central claims were misleading or wrong.

Thousands of pairs of jeans would have the same feature.

The barcode pattern is unique because the stitching varies between pairs, Vorder Bruegge wrote.

The number of stitches per inch along a seam is much the same from one factory floor to another.

you’ve got the option to see that in the article.

Jeans comparisons could help ongoing investigations, but they arent conclusive evidence.

It wouldnt stand scrutiny today, Bell wrote.

The evidence gathered against McKreith wasnt overwhelming.

Vorder Bruegge got the case.

FBI image examiners routinely testified those clashing patterns were individual characteristics that can identify a garment.

He concluded the defendants shirt matched the robbers at eight different points,court records show.

And then he calculated the probability that a random shirt not McKreiths would match as precisely.

If two features matched, the random match probability dropped to one-tenth of a percent.

Prosecutors used Vorder Bruegges testimony in an effortto erase any doubtabout McKreiths guilt.

John Howes, McKreiths defense attorney, asked the court to suppress the image analysis as unscientific.

But he didnt see the article before they were in court, and he never read it.

The judge ruled Vorder Bruegges testimony met the Daubert standard and was admissible.

The decision enshrined the FBI units techniques and testimony as reliable scientific evidence.

Theyre all the same shirt,he said.

Vorder Brueggedirectly contradicted his reportin court.

The jury convicted McKreith of seven robberies.

Hes exhausted his appeals, most of which attempted to dispute the FBI Lab findings.

The statisticians who reviewed Vorder Bruegges materials for ProPublica said the examiners calculations cannot be correct.

Many problems in the examiners testimony went unnoticed, or were simply unknown, during trial.

It would be one in thirty-five times one in thirty-five.

But to simplify things and to be conservative, I prefer to use one in thirty.

Thirty times thirty is nine hundred.

Vorder Bruegges testimony in U.S. v. McKreith.

The photographed shirts in the McKreith case were curved around shoulders and arms.

On the stand, Vorder Bruegge didnt mention that his precise measurements might be inaccurate.

It may be an honest belief, Kaye said, though terribly flawed.

Scars, tattoos and chipped teeth make identifications straightforward.

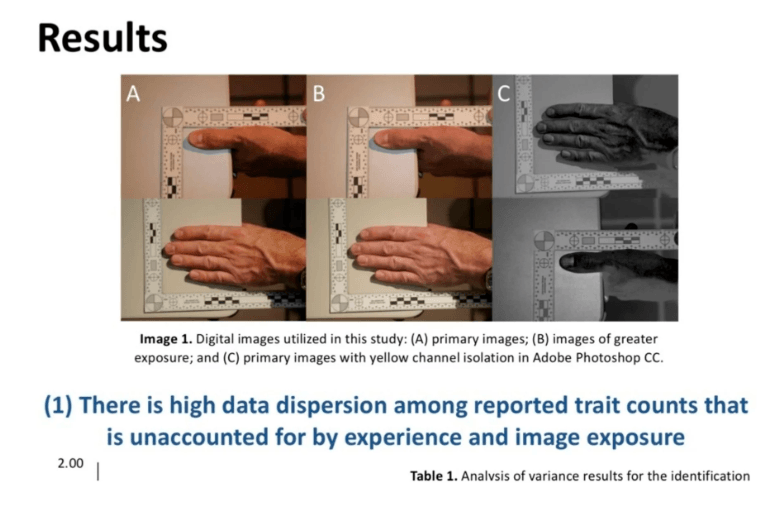

The same principle has been applied to the back of suspects hands.

Christopher Iber, an examiner in the image unit, received the evidence and set about comparing hands.

Iber did not respond to interview requests.

They served together on a group writing standards for facial identification by law enforcement.

Flynn believes adding skin marks to the formulas can help their accuracy.

The FBI Lab had already been using those features in image analysis, so Vorder Bruegge lent his experience.

An early finding disputed the FBIs contention that each identical twin had his or her own unique features.

Researchers documented thattwins share frecklesmuch the way they share all other genetic traits.

But the study continued, next examining how consistently the computer found skin marks compared with the human participants.

The algorithm did badly, but the humans werecompletely unreliable.

All the participants came up with different sets of freckles and blemishes.

… individual observers perceive facial marks differently over time and the annotations are inconsistent.

… different observers view facial marks differently, leading to inconsistency.

Article detailing the results of a study on the use of facial skin features to distinguish between identical twins.

Vorder Bruegge was one of the co-authors.

5, October 2012)

The study had troubling implications for the FBIs image unit.

Science demands consistent results.

In 2012, the Defense Forensic Science Center, the U.S. militarys crime laboratory, tested hand comparisons.

Researchers intended to develop an algorithm that could identify people the way the FBI Lab does.

The results wereunexpectedly poor.

Most damning, the trained forensic scientists were no more reliable than students.

The military researchers published their results in the Journal of Forensic Sciences in November 2015.

Use in court first, validate second.

That did not dissuade the FBI Lab.

A bureau image examiner testified onthe results of a thumb comparisonin a May 2017 child pornography trial.

But Vorder Bruegge had taken notice.

Boyd said he expected the results would bolster the hand comparison technique.

Instead,they debunked the methoda second time.

Examiners were no better than interns.

All were inconsistent and imprecise.

I was fascinated by how the human eye is still outperforming the algorithm, Boyd said in an interview.

Yet what we found here is the human eyes dont necessarily agree.

Vorder Bruegge and the other examiners had muted reactions when he delivered the study results, Boyd said.

There was just kind of a, OK, well, thats good to know, he said.

This pieceoriginally appearedat Pro Publica, and was re-published with permission.