Typing is one of the most common things we do on our mobile phones.

A recent survey suggests that Millennials spend48 minuteseach day texting, while boomers spend 30 minutes.

Since the advent of mobile phones, the way we text has changed.

Functions such as autocorrect and predictive text are designed to make typing faster and more efficient.

But research shows this isnt necessarily true of predictive text.

Astudypublished in 2016 found predictive text wasnt associated with any overall improvement in typing speed.

But this study only had 17 participants and all used the same punch in of mobile unit.

Participants were asked to copy sentences as quickly and accurately as possible.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

Participants who used predictive text typed an average of 33 words per minute.

Breaking it down

Its interesting to consider the poor correlation between predictive text and typing performance.

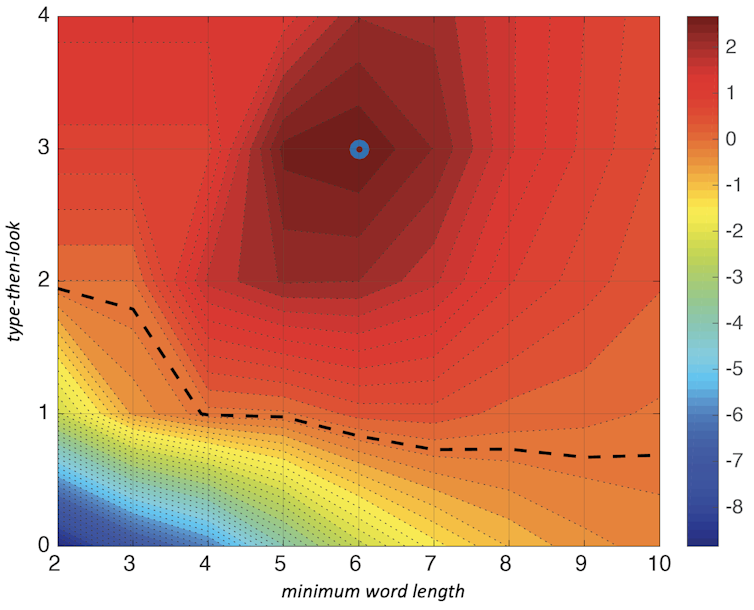

We built a couple of fundamental parameters associated with predictive text performance into our simulation.

We estimated this at 0.26 seconds, based onearlier research.

We fixed this at 0.45 seconds, again based onexisting data.

Beyond these, theres a set of parameters which are less clear.

These reflect the way the user engages with predictive text or their strategies if you like.

The first is minimum word length.

This means the user will tend to only look at predictions for words beyond a certain length.

You might only look at the suggestions after typing the first three letters of a word, for example.

Although we dont have data on the average perseverance, this seems like a reasonable estimate.

What did we find?

The blue is when its least effective.

The blue circle shows the optimal operating point, where you get the best results from predictive text.

So, for the average user, predictive text is unlikely to improve performance.

And even when it does, it doesnt seem to save much time.

The potential gain of a couple of words per minute is much smaller than the potential time lost.