Weve all but won the argument onclimate change.

The facts are now unequivocal and climate denialists are facing a losing battle.

Now, the second, even more challenging phase of the struggle begins what exactly to do about it.

Without damaging our alreadyfragile biodiversity?

Without threatening ouralready pollutedwater and air?

Proposed solutions to deal with climate change vary enormously in terms of their benefits and pitfalls.

Take my own research field of landscape ecology.

Some proposals are overwhelmingly positive.

But other solutions have worrying trade-offs.

It’s free, every week, in your inbox.

And other nature-based solutions are a bit of a mixed bag.

As you might see, it gets complicated very quickly.

Which path should we take?

We need applied, solutions-oriented science.

You may detect a certain urgency in my tone here.

Its just that time is getting awfully short.

We now have just over ten years left, and in the last year we have actuallyincreased global emissions.

This is not fit for the purpose of aclimate emergency.

This isnt the only way of doing things.

In the past, governments have worked much more closely with scientists to respond to emergencies.

State-funded research during the Cold War, meanwhile, led to the development ofthe internet.

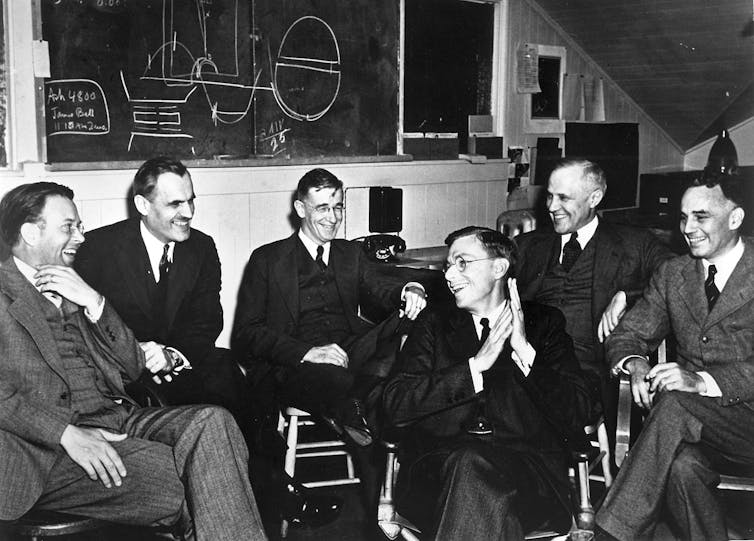

A 1940 meeting of Manhattan Project scientists.

So what is the answer?

This involves a strategic policy design, drawing on foresight methods, and integrating across departments.

I am currently advising them on the design of this program.

Yet there is still a missing player here: civil society.

Recently, civil society groups such asExtinction Rebellionhave called for citizen assemblies to deal with climate change.

They recommend that scientific experts should be on these panels.

Yet no single expert can provide all the answers.

This requires nothing less than a vast mobilization of scientific knowledge on a scale greater than ever yet achieved.