All around the world, there is an extreme gender imbalance in physics, in both academia and industry.

Examples are all too easy to find.

In Burkina Fasos largest university, the University of Ouagadougou, 99% of physics students are men.

In Germany, women comprise only 24% of physics PhD graduates creeping up from 21% in 2017.

No women graduated in physical sciences at the University of El Salvador between 2017 and 2020.

Australia fares little better.

And the hits keep coming.

40% off TNW Conference!

But that figure is much lower in physics and in the higher echelons of academia.

Clearly, this gender imbalance urgently needs to be fixed.

As the conference progressed, somedistinct targets for actionemerged.

A further 48% of women (and 28% of men) leave before the associate professor level.

This can be deep-rooted, with discrimination at the earliest levels of education.

University-educated women often find themselves blocked from research funding or leadership positions.

Showing the way

Despite the deeply ingrained challenges, there are some signs of progress.

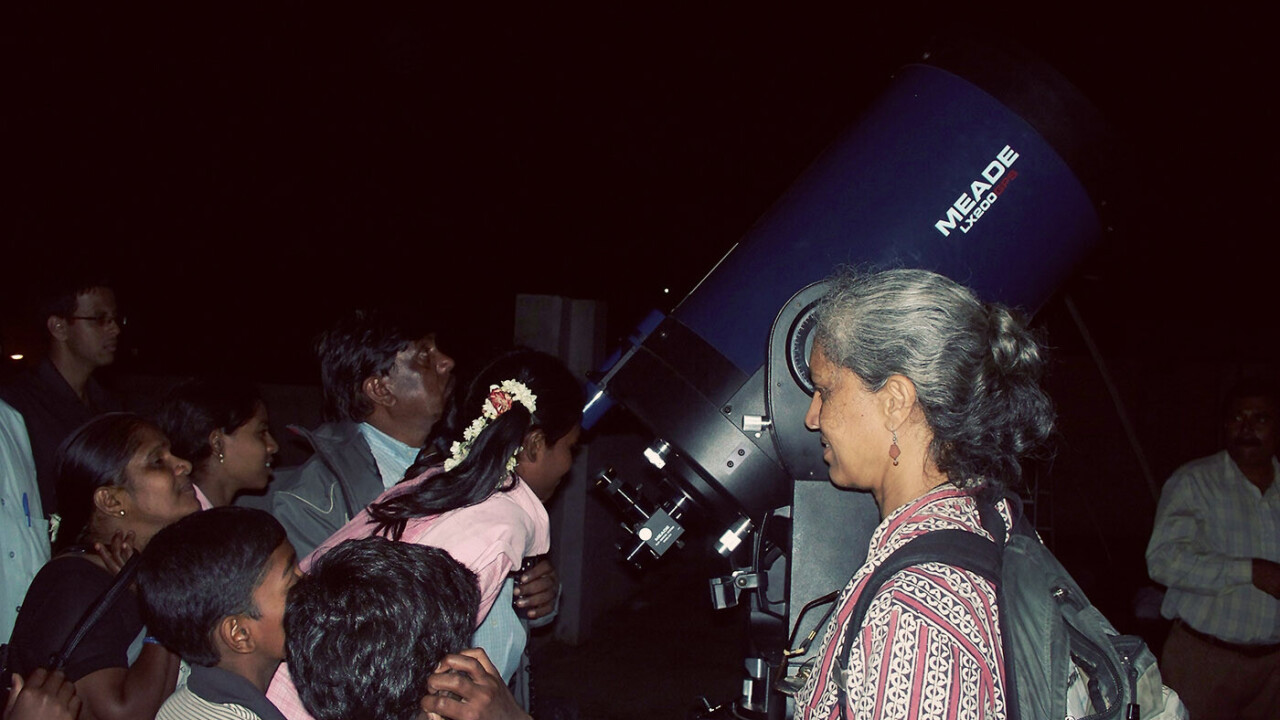

Two standout nations are Iran and India.

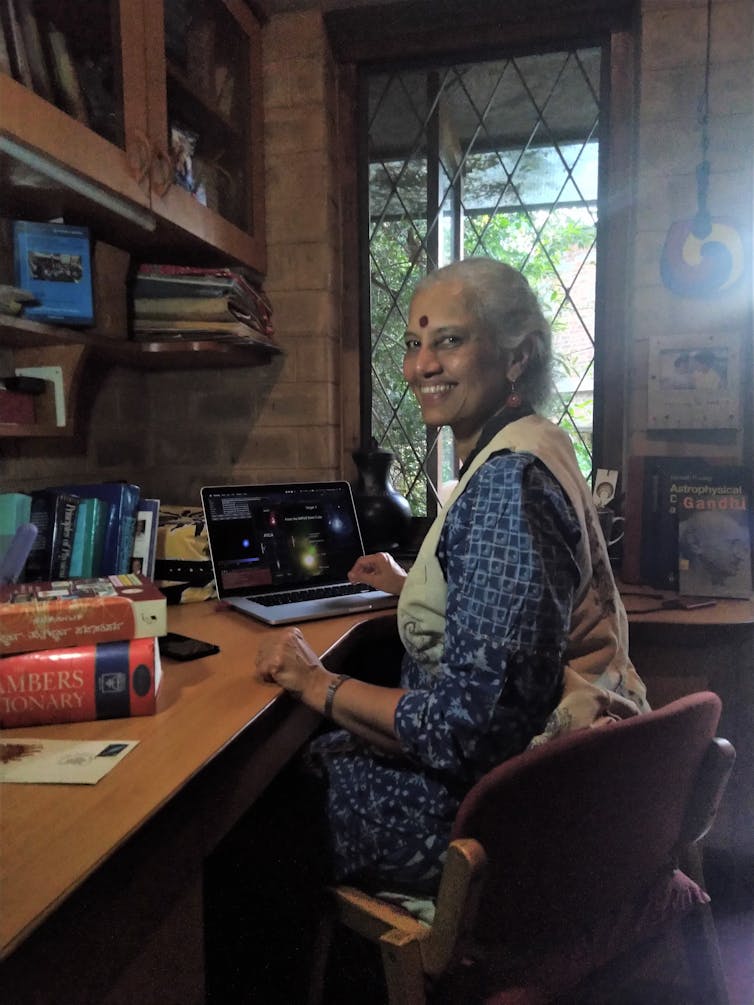

Prajval Shastri at work.

That way, it will emerge as a better and more inclusive profession for everybody.

Boys and girls alike deserve to see more role models from all marginalized groups doing physics.

The conference generated aseries of recommendations, which we will now share with the wider physics community.

We welcome the debate that will follow.