Look at that picture over there!

Heres the Earth coming up.Wow, that is pretty.

and life returned to the world .

.It has been called

Oh thats a beautiful shot.

the most important picture of the 20th century.

He left industry to launch an environmental-surveillance nonprofit calledSkyTruth.

Such is the power of a transformative shift in perspective enabled by a major leap in engineering.

Ranchers are stapling health-monitoring microchips to their livestock.

Beekeepers are sticking wireless sensors into their hives.

Farmers are planting high-tech electronics into the soil along with their crops.

We are on the curling edge of the wave, Amos says.

This new instrumentation is more about seeing what people are up to in the environment, he says.

The promise of this convergence in technology lies in imposing radical transparency on corporate activity and supply chains everywhere.

Or so one would hope.

Radical transparency in our online lives has frayed, not tightened, the fabric of societies.

And now, in the unrelenting march of technological monitoring, things are getting real.

And those who are being observed and recorded are not the customersthey are the products.

Does any of this sound familiar?

Yet history is not destiny.

Surprisingly, experts say that might not be as hard as it sounds.

One can now tag, say, a whaling ship and follow it from port to port.

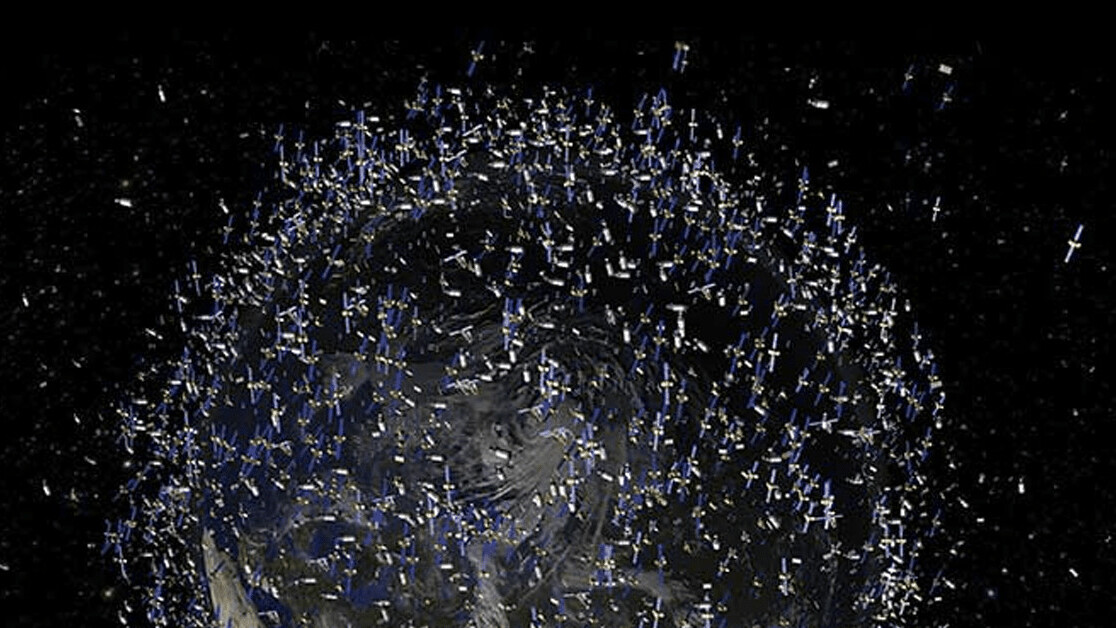

Europes Copernicus program has fielded six Earth-observing satellites, called Sentinels, since 2014.

It plans to expand the fleet to 30 within the next decade.

Last year, China added six high-resolution optical and infrared imaging satellites to its fast-growing constellation.

The instrumented Earth

A thickening flock of Earth-observing satellites blankets the planet.

In the US, the most dramatic growth in environmental surveillance is happening in the private sector.

San Franciscobased Planet Labs has launched 331 Earth-observing satellites since it spun up in 2013.

(For comparison, 173 satellites owned by governments were operating at the start of 2016.)

The company now collects 300 million square kilometers of imagery every day.

Thats nearly three-fifths the surface area of the Earth.

Views from the newest Chinese satellites are thought to be sharper still.

Such surveillance works only when skies are sunny.

That kicks open some doors, Amos says.

Were just now seeing the beginning of what is going to become possible, he says.

Amazon makes all data from Landsat 8 freely available on its cloud storage service.

Scroll over northern California in the viewer, and the demise of Goose Lake is unmistakable.

press the lake, and year-by-year measurements reveal that the 2008 drought sounded its death knell.

Access to space has become cheap enough that better-funded nonprofits can now put their own birds into the sky.

Last winter, autonomous sailing robots built bySaildroneset off from South America to circumnavigate Antarctica.

One of the biggest challenges in environmental surveillance has been digging through haystacks for elusive needles.

Society already struggles with too much data, not enough information, Amos says.

And this is certainly happening in remote sensing as well.

After many years of false starts, artificial intelligence finally seems ready to help solve this problem.

Hunters often slipped past them.

It worked so well that they are now using it in national parks in Botswana and other African countries.

Global Fishing Watch has used AI to distinguish fishing vessels from cargo and naval ships.

All of these examples, and many others like them, are tremendously encouraging.

The corporations building these technologies are creating new kinds of data, new use cases, new users.

But they are companies, so they are selling that data to make a profit.

And the revenue generated by environmental protection projects shows up on their books as little more than rounding error.

That is essentially the mistake we made with social media.

Some of those exposes have triggered official responses.

Environmental exploitation remains highly profitable, and profitable businesses find ways to protect themselves.

The same can be said of the technology industry.

How much more valuable would it be to occupy the position of gateway to the planet?

Planet Labs has been open about its long-term commercial strategy.

None of this is necessarily a bad thing.

Most have not yet been conceived.

And recall how in 2017 Google tracked Android users, even when they had disabled location sharing.

The day may arrive when going off the grid is no longer possible.

Sixty percent of Maxars business comes from the US military, she notes.

Planet Labs has earned tens of millions of dollars selling imagery to the US National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

Governments have often demanded exclusive access to the imagery they purchase.

Thats definitely a concern, Woods says, particularly for elephants, rare whales, or rhinos.

One result, he observes, is that regulations are consistently co-opted.

Instead of promoting the common good, theyre aimed at promoting some private agenda.

Watching the watchers

The good news is that none of these bad things has happenedyet.

Nor are they inevitable.

Several models suggest how to prevent environmental surveillance from going sideways.

Space exploration and scientific research offer two useful examples.

And the wireless-communications and financial industries provide complementary ideas worth considering.

So far, 35 countries have lofted Earth-facing satellites.

Everyone with a reasonably legitimate need gets to access low-Earth orbit and put hardware in space, Amos notes.

Its just as important that there wont be shutter control imposed on [those] remote-sensing systems.

Theres no avoiding the fact that we look at the world through a prism.

But we should be free to switch prisms and compare different perspectives.

Scientific research has long embraced a similar principleand it has been one of the greatest strengths of that enterprise.

Similar rules could protect sensor data against undisclosed conflicts of interest and outright fraud.

The volume of data presents one hurdle to meaningful open access.

NOAA satellites alone generate 20 terabytes of data daily.

One petabytea billion megabyteswould take several years to download over a fast fiber-optic broadband connection.

Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and others already offer competing cloud-computing platforms that can do the job.

But this raises a second, thornier issue.

Space is a global public commons, Amos points out.

The fees could then help cover the costs of hosting the data for all to use.

The environmental bad guys already have ways to do what they want, Woods says.

As long as the information stays open, I believe these tools will benefit the small players more.

He is a contributing editor withScientific American and editorial director at Intellectual Ventures.

His work has appeared inScience, Nature, Discover, IEEE Spectrum,andThe Economist.