One economic alternative lies just offshore.

On its seabed are potato-sized rocks called polymetallic nodules which containnickel, copper, cobalt and manganese.

These formed over centuries through the accumulation of iron and manganese around debris such as shells or sharks teeth.

To date, ISA hasapproved 19 exploration contracts, 17 of which are in the CCZ.

A Canadian company,The Metals Company(formerly DeepGreen Metals) hascontractswith Tonga, Nauru and Kiribati.

Environmental organisations and scientists havearguedfora moratoriumon mining until more extensive research can be done.

In April 2021, Pacific civil society groups wrote to the British governmentseeking support for a moratorium.

But time is running out.

From exploration to extraction

Work towards this framework has been ongoing since 2014.

Exploratory licences are regulated by the ISA.

Without an agreed code, extractive ones are not.

Even if a consensus were reached, enforcing environmental safeguards would be difficult.

There are also few, if any, physical boundaries between one mining area and another.

The effects of mining on different ecosystems and habitats might take time to manifest.

International consensus on a moratorium is unlikely too.

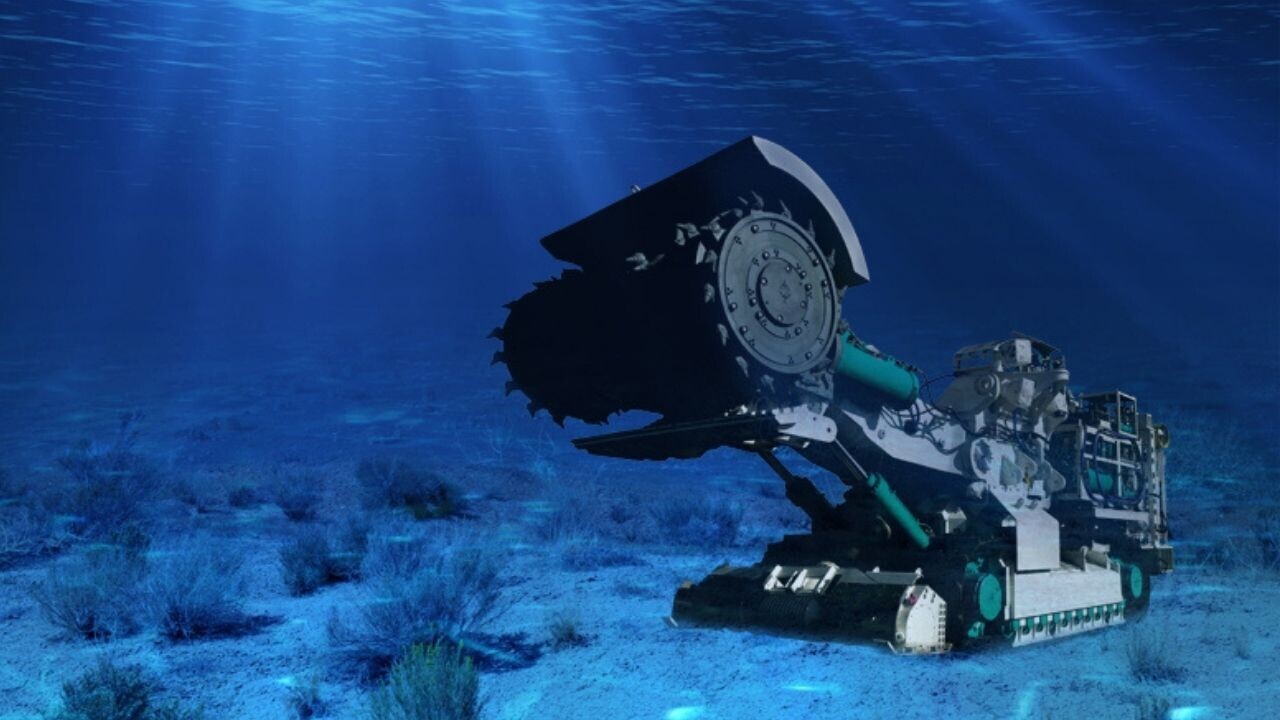

Mining companies have ploughed a lot of money into developing technology for operating at these depths.

They will want to see a return on that, and so will their investors.

Pacific island states find themselves on the horns of a dilemma.

They are among the countries most vulnerable to climate change and so support strong action.